If you wish to discuss the contents of this page Fred's email address is at the bottom of the page

Featuring photos of Blyth Harbour, Blyth Staiths, Blyth North & South sheds plus aerial photos...

This is the true story of a young train spotter metamorphosing into a fat, baldy bloke driving a Flying Banana! Retired railwayman, Fred Wagstaff recently made contact (via the Guest Book page) seeking old  photographs of North and South Blyth Sheds.

photographs of North and South Blyth Sheds.

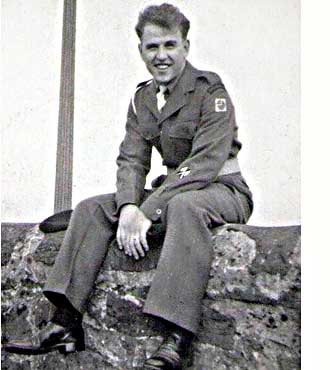

Being a relative newcomer to web hunting - and, at 72 years of age, finding the task somewhat daunting - he wondered if someone could point him in the right direction. During our exchange of emails it struck me that Freddy's witty anecdotes ought to be shared with others, and I'm pleased he agreed to write something about his 49 years service with British Railways, starting as a cleaner at Bournville in 1953.

From there he moved north to South Blyth, made fireman at North Blyth, then following National Service and closure of North Blyth shed, he moved to Cambois MPD, and after 30 years in the line of promotion finally made Driver at Gateshead MPD.

But I'll let Freddy take up the story...

When I was a young lad during the Second World War, the Luftwaffe flattened our house in Gooch Street, Birmingham during a bombing raid over the Midlands. With more air raids imminent, I was evacuated to the little village of Ashwel near the town of Oakham in Rutland to live with my Auntie Nelly.

I must have been about eight years old at the time and the highlight of the day was the arrival of the local  pick-up goods at Ashwel Station sidings to drop wagons off and pick up empties. One day, as I sat on the fence watching the proceedings with great interest, I realized the driver was the same man I had seen several times previously. After the job was done he gave me a cheery wave, then lighting his pipe, climbed down and asked - 'Are you interested in locomotives?'

pick-up goods at Ashwel Station sidings to drop wagons off and pick up empties. One day, as I sat on the fence watching the proceedings with great interest, I realized the driver was the same man I had seen several times previously. After the job was done he gave me a cheery wave, then lighting his pipe, climbed down and asked - 'Are you interested in locomotives?'

I replied that I was. His next question excited me more than anything before or since - 'Do yer fancy a look inside the cab?'

I flew over to the loco and climbed onto the footplate for the first time. My eyes must have been the size of dinner plates as I took it all in. The fireman gave me a big grin - 'Are you the new driver then?' he laughed, then went on to explain all about the controls and lubricators.

I was absolutely spellbound, and from that day on I no longer wanted to be a Spitfire pilot. I wanted to be an ENGINE DRIVER, and that was that…

After leaving school at fifteen, I was put to work on the assembley line at a factory in Kings Norton, but I found the repetitive work of assembling steering columns for motor cars a soul destroying job. After six weeks, I badgered my Mam about applying for a job at British Railways. She knew I was miserable, so in spite of earning £5 6 shillings per week at the factory - a considerable amount for a young lad in those days - she finally relented and let me hand in my notice.

I duly signed on as an engine cleaner at Bournville Loco Depot for the princely sum of £2 five shillings a week. Mam got the two pounds and I got the five shillings, most of which was spent on bus fares. It wasn't until I built a pushbike out of bits 'n' pieces - begged, borrowed or otherwise 'acquired' - and cycled the 8 miles to the shed that my cash flow improved.

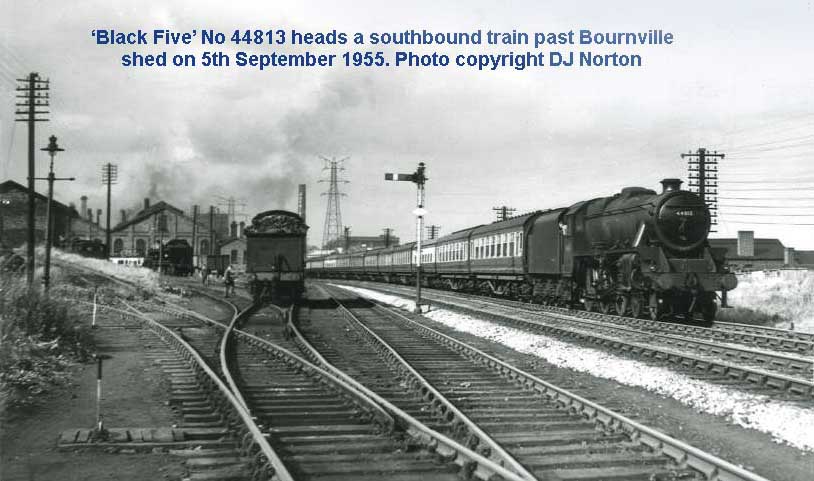

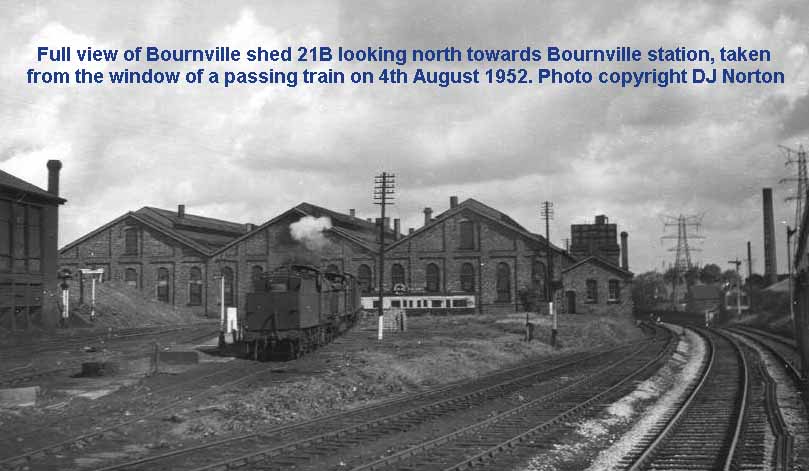

(Above-Below) Surfing the Internet for photos of Bournville shed, I came across Mark Norton's excellent website compiled as a memorial to his late father, Dennis John Norton. The quality of his dad's photography is superb and I immediately sent a link to Fred, who replied - 'I've been sitting here for ages devouring the photographs of Bournville Shed, remembering all sorts of things from all that time ago. I cannot tell you how it felt when I opened the site, and there it was, exactly as I remembered it - the little Jinties standing about the place and a calm sort of feeling all around. Every now and then the 'Pines Express' would rocket past with a 'toot on his flute' and well wound up. Sometimes it would be a 'Jubbly' or a Capproti Five and once I remember two 4P Compounds with that unique roaring beat of theirs. Happy days, or should that be spelt daze! To savour more of DJ Norton's photos taken around the Birmingham area click here and give yourself enough time to browse the rest of the site...amazing!

The Foreman Cleaner at Bournville was a little chap with a loud voice, and some of the more senior lads said that inside him was a big bloke trying to get out! He spent most of his days strutting around the shed barking orders like a Regimental Warrant Officer. But there was no need! We were doing a job that we all enjoyed.  One of the Passed Cleaners told me that the reason he was so grumpy was because a particular 'private part' of his anatomy had been shot away during the First World War, so he was unable to fulfill his marital duties in that department. I was told that if I didn't believe it, I should go and ask him myself. I politely declined to do anything of the sort. I'd have put myself in a position of grave and imminent peril in such a fashion, probably ending up with a hefty clip around the ear for my trouble!

One of the Passed Cleaners told me that the reason he was so grumpy was because a particular 'private part' of his anatomy had been shot away during the First World War, so he was unable to fulfill his marital duties in that department. I was told that if I didn't believe it, I should go and ask him myself. I politely declined to do anything of the sort. I'd have put myself in a position of grave and imminent peril in such a fashion, probably ending up with a hefty clip around the ear for my trouble!

Anyway, after six enjoyable months, my Mam got married again and we moved to Northumberland, and I got a transfer to South Blyth Shed. It was a totally different world…my time at South Blyth always struck me as being a learning time. This was because I spent more hours working on the more practical aspects of footplate life and less time using paraffin rags and scrapers. I learned the importance of lubrication around all the oiling points and how to make tail- trimmings that fed oil by capillary action to where it was needed. I was taught how to light fires in fireboxes without being burned alive and how to clean loco fires with a ten foot long scar shovel. I learned how to clean smoke boxes and ashpans, and how to set a loco for oiling so that all lubrication points were easy to reach.

I also learned that in 3-card brag an 'Ace-King-Queen' of diamonds doesn't stand a chance against 'Three Fives' - it was a lesson well learned when I lost a week's wages and had to borrow three pounds to give my Mam my keep.

Then there was the BOOK OF RULES AND REGULATIONS and the APPENDIX TO THE RULES AND REGULATIONS, all of which had to be learned before being passed for firing duties and becoming a Passed Cleaner. Since you were required to do this in your own time, the lads arranged an excellent 'Mutual Improvement Class' after work for anyone wishing to attend.

The meetings were held over a few pints of Black and Tans at the British Railways Staff Association Club (BRSA) and some lively discussions took place. One time it was so lively that two fat lips and a black eye were observed at the shed next morning! As it turned out, both lads were wrong and it was all for nothing in the end.

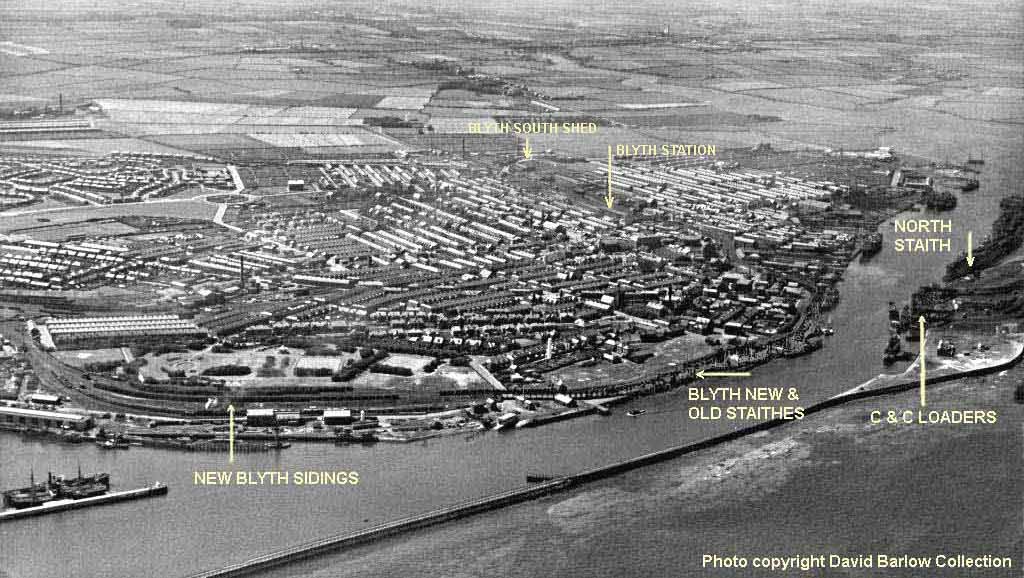

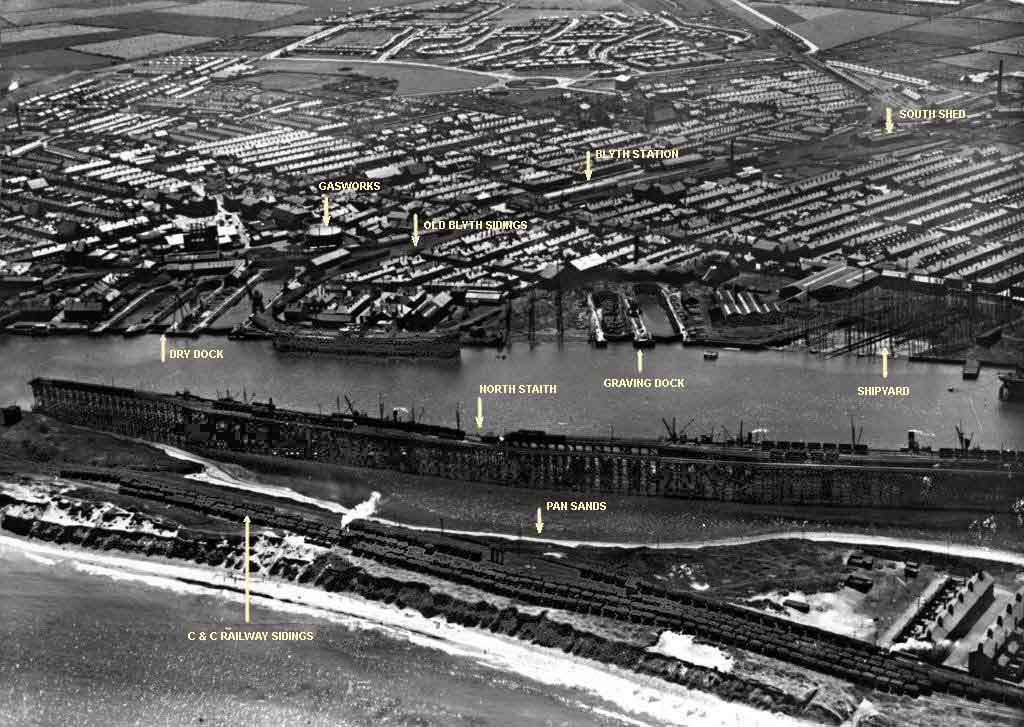

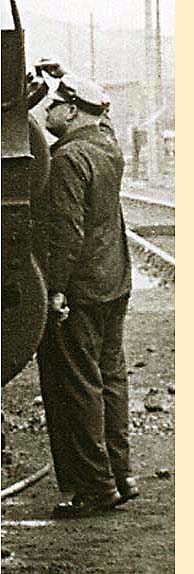

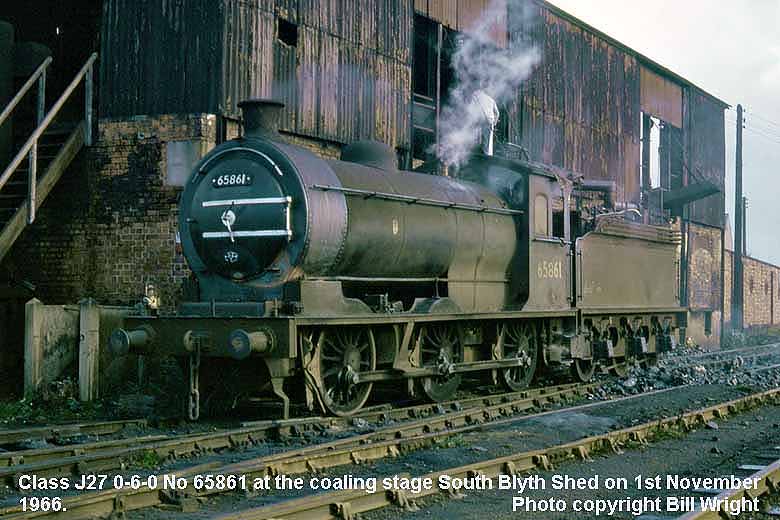

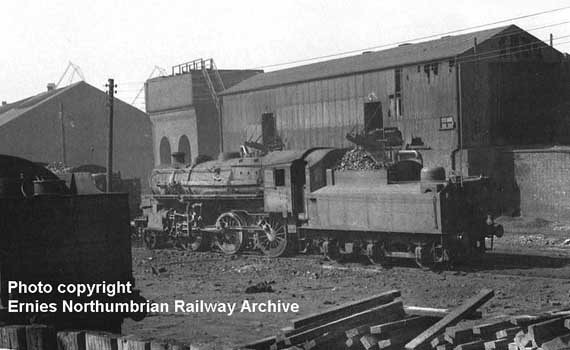

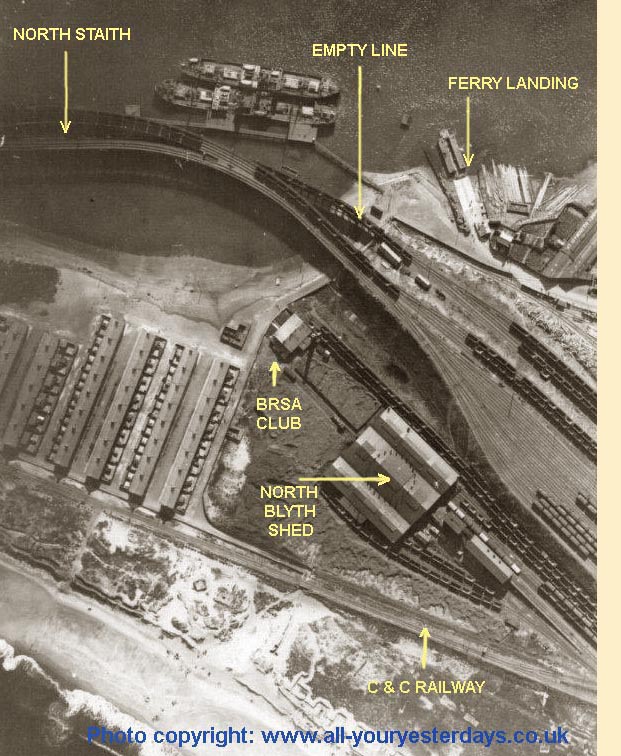

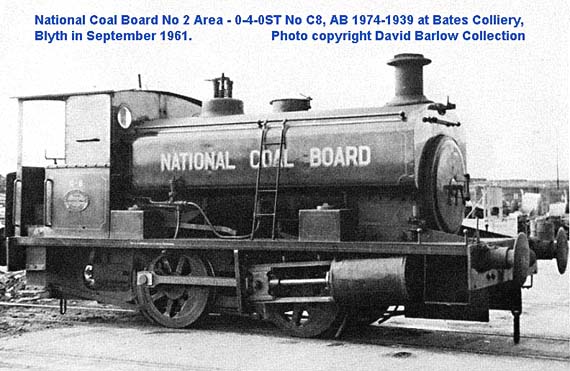

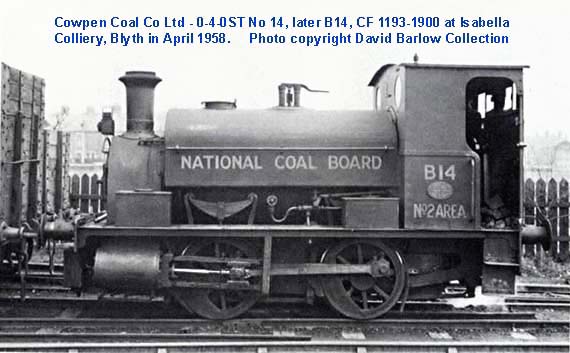

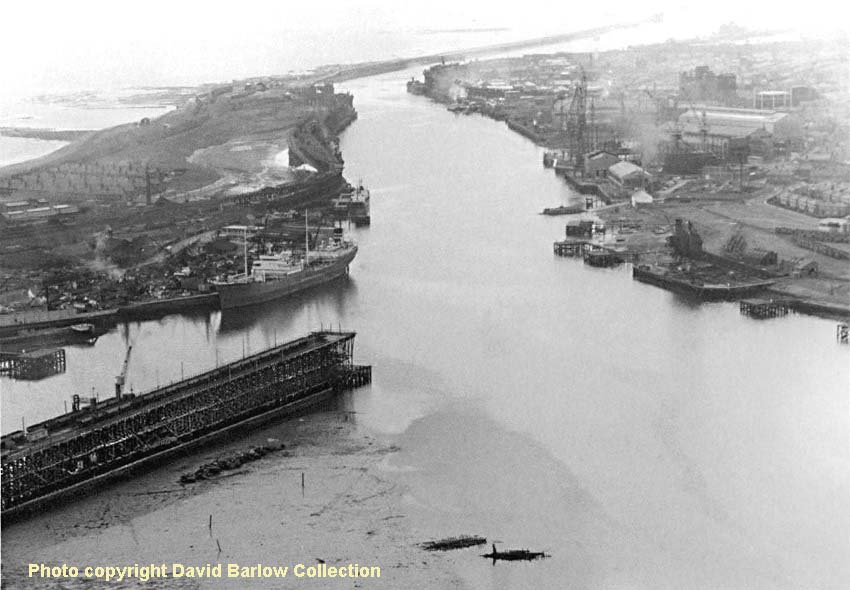

(Above-Right-Below) A superb aerial photo from the David Barlow collection of Blyth Harbour, which I hope will show you the whereabouts of the various maritime photos featured elsewhere on this page. (Right) Link to Phil Hodgett's page describing the history of the Port of Blyth. (Below) This shot at South Blyth shed is unmistakeably from Bill Wright's Flickr stable. It captures the final days of steam perfectly; it certainly hit a nerve with Fred - 'Working on the coal stage was hard graft and we really earned our wages, spending long hours shovelling coal out of sixteen ton wagons into half ton barrows. After the barrows were full to the top and lined up for emptying into loco tenders, we swept around the stage until everything was neat and tidy, then a loco would arrive and take on coal from four or five full barrows and the whole exercise would start all over again!' Visit Bill's 'Rail Cameraman' page 57.

(Above-Right-Below) A superb aerial photo from the David Barlow collection of Blyth Harbour, which I hope will show you the whereabouts of the various maritime photos featured elsewhere on this page. (Right) Link to Phil Hodgett's page describing the history of the Port of Blyth. (Below) This shot at South Blyth shed is unmistakeably from Bill Wright's Flickr stable. It captures the final days of steam perfectly; it certainly hit a nerve with Fred - 'Working on the coal stage was hard graft and we really earned our wages, spending long hours shovelling coal out of sixteen ton wagons into half ton barrows. After the barrows were full to the top and lined up for emptying into loco tenders, we swept around the stage until everything was neat and tidy, then a loco would arrive and take on coal from four or five full barrows and the whole exercise would start all over again!' Visit Bill's 'Rail Cameraman' page 57.

I eventually passed the examination on rules and regulations and became a passed cleaner. This meant I'd be available for any firing jobs that cropped up, such as covering for men being off sick or on holidays. There was one very nasty proviso in the manning agreement called the 'twelve and thirty-two hours clause', which stated that a man working a higher grade turn of duty could be signed on after twelve hours rest or laid back thirty-two hours to facilitate the manning of vacant turns.

In reality this meant that your start time at the shed could be 4am on Monday morning and you might end the week on the Saturday signing on at 7.30pm for the last passenger turn. In fact, a passed fireman and a passed cleaner nearly always worked the last passenger turn. This was because the regular men on this turn would stop at nothing to wangle Saturday night off!

At first I wasn't bothered too much because I enjoyed working on the Main line, but later on I began courting and after that - well, let's just say I started doing some wangling of my own and achieved quite a high level in the 'art'…

I say art because you had to be crafty to get away with it. Some of the excuses the docket clerk heard were out of this world. One bloke's Granny died four times!

This prompted the docket clerk to enquire how many Grannies he had and whether they were in good health or not!

This is the same daily docket clerk who complained bitterly about one of the drivers dying unexpectedly. This meant the clerk had to redo the whole docket for the next week.

Someone stuck a notice on the wall stating-'DRIVERS CONTEMPLATING DYING SHOULD FIRST SEEK THE DOCKET CLERKS APPROVAL AND THEN DIE, PREFERABLY IN THEIR OWN TIME, AND AS FAR AWAY FROM THE PREMISES AS POSSIBLE!'

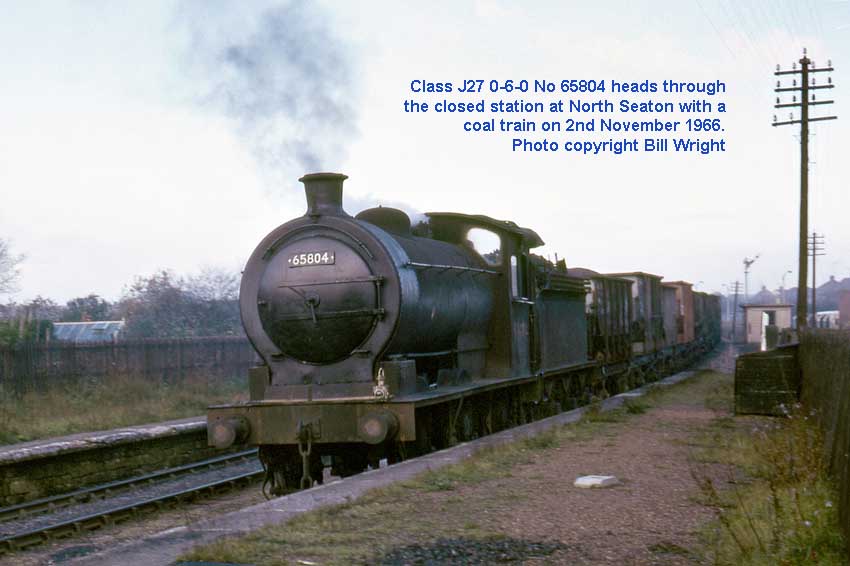

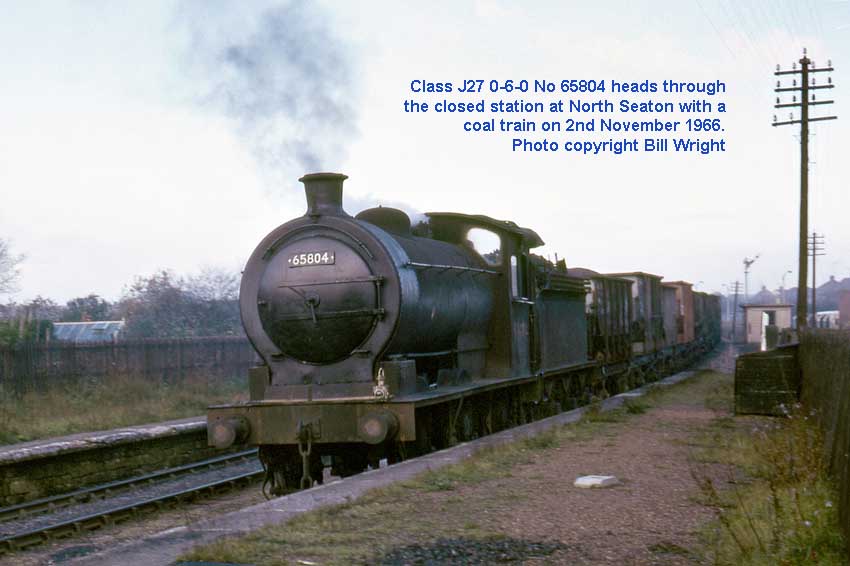

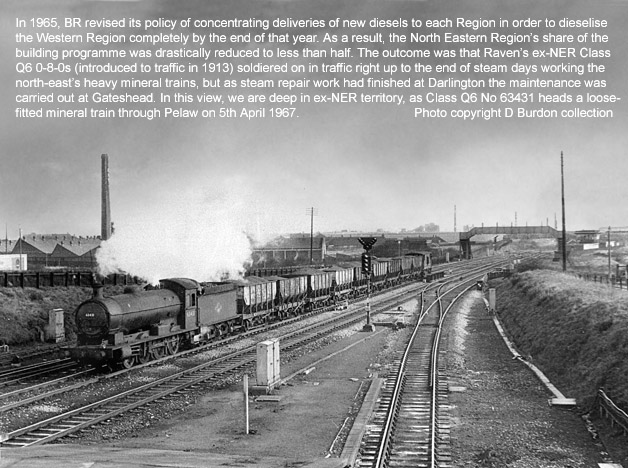

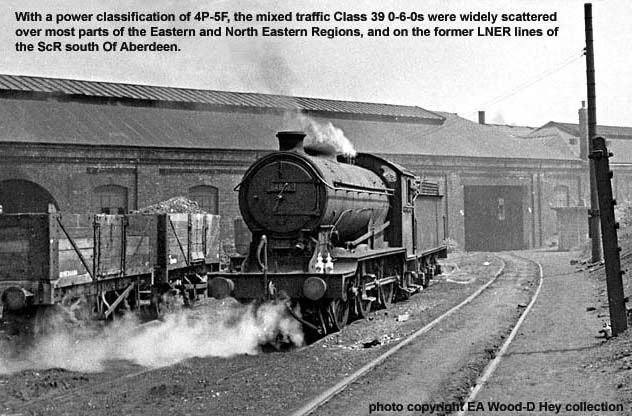

(Above-Below) When Fred saw shots of steam in the North East on Bill Wright's Flickr site, he said - 'Bill Wright's colour photos bring many back happy memories. I wish I had a shilling for every time we passed through North Seaton. There was a huge bakery there that made real bread in coal-fired ovens. Ashington Colliery was, of course, the biggest deep mine in Europe, with five shafts, and if I remember rightly, Ashington signal box could route you into the colliery, or onto the NCB line to Linton opencast/Linton colliery/Ellington colliery and Lynemouth colliery. If you kept going you went in a big circle back to Ashington box via Woodhorn colliery and signal box, where trains were routed to Newbiggin on a single line to the colliery and the station. To put it another way, Ashington box could route you three ways - colliery/NCB/Main line to Woodhorn for Lynemouth and Newbiggin.'

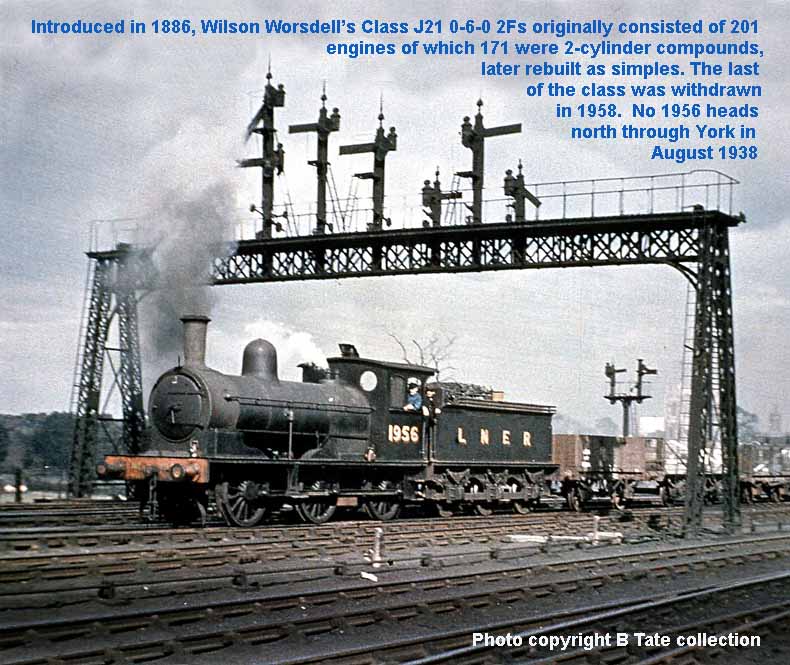

(Above-Below) Sporting a 52F shedplate on the smokebox door, push-pull fitted G5 Class 04-4T No 67273 arrives at the seaside terminus of Newbiggin-on-the Sea, a favourite holiday destination situated deep in the Northumberland coalfield. The branch fell vicyim to the Beeching axe in November 1964. (Below) South Blyth's allocation of locos was mostly Wilson Worsdell's NER designs, including Class J27 5F 0-6-0s for mineral traffic, the mixed-traffic Class G5 0-4-4Ts for passenger turns to Monkseaton-Manors-Newcastle and Newbiggin, Class J77 2F 0-6-0Ts for shipping, staithes and pilots, and Class J21 0-6-0 2F for local pick ups and the Rothbury pick up. Incidentally, the Rothbury engine No 65033 is now at Beamish Museum. The G5 was a great little engine; it had to be fired little and often. If you gave it too much coal, you might be short of steam and losing time. During my spell as a cleaner at South Blyth, the G5s were among the engines we were required to clean. I recall one driver who willingly turned up at the shed two hours before he was due to sign on for his shift, and set about cleaning his engine with tallow and paraffin rags. He buffed the tank sides till they gleamed and the pipework shone like a Guardsman's buttons. The number was 67361 and it was his baby; it was the only one with extended sidetanks I ever saw. I never did find out the reason for them.

(Above-below) The Class J27 was a hungry horse. Some engines could give you a very hard time, others were a pleasure to work with. A lot depended on the driver, of course - and, broadly speaking there was only one 'lunatic' driver at South Blyth. He did more damage to locos and buffers than twenty other men on the network put together. A very exciting day was guaranteed when working with him - you only needed to put a shovel of coal by the fire hole door... it got sucked in and spat out of the chimney still burning! One of his most notorious stunts was to destroy a signal box only two weeks after it had been rebuilt - the signalman had a nervous breakdown! Whenever he was running into a bay platform his fireman would open the cab door ready to bail out! (Below) The J21 was a tired man's dream machine, and you could keep steam with your hands in your pockets - all except when the 'lunatic' driver had a hold and then it was like Pearl Harbour all over again!

A CLOSE CALL AT SOUTH BLYTH!

As time went by I developed into a right cocky so-and-so. I was over-confident, believing I had a surefire knowledge of the job. My attitude was that I could handle any situation that may crop up. Even when the senior men offered me good, sound advice - men who had been doing the job for twice my lifetime - I thought I knew better than them - STUPID, STUPID BOY!! It wasn't until a near-fatal accident occurred at South Blyth shed that I came to my senses. I'll never forget that day for as long as I live…

…I was working a Shed Relief turn with a good mate and, through my own sheer stupidity, went to move an engine that was being oiled in preparation for duty. I should explain that there wasn't any 'NOT BE MOVED' boards on the lamp brackets nor on the regulator, but at the same time I knew I should have shouted 'All Clear Number XXXXX' before I went on the footplate. I hadn't realised the driver was underneath oiling the big ends. When I put the loco into fore gear, the driver saw the gear move and in an instant dropped down into the pit. He escaped mutilation by the skin of his teeth. Had he waited another second, I'd have put the steam on, moved the engine and killed him…

When I saw him emerging from the pit shouting and swearing, I was in a state of shock, I couldn't move, mesmerised at the stupid action I had been responsible for. He leaped into the cab, grabbed my overalls and dragged me out, then lifted me off my feet and pinned me against the wall, his nose an inch from mine - 'If you ever do that to anybody ever again,' he roared - 'I'll f… g kill you, you stupid b……d!'

I was shaking in my boots, though not from a fear of getting a good hiding, which I richly deserved, but from the enormity of what I had just done. When a crowd gathered, my mate stepped in to defuse the situation and told me to make myself scarce in the field next to the shed while he talked to the driver. Afterwards my mate came over and gave me the 'mother and father' of all the dressing downs I've ever had, even in the army. And boy! - did I listen! He told me the story of a young fireman working a passenger turn who, for one reason or another, had stepped in between coach and loco before it was fully buffered up. He got caught somehow and was killed instantly - 'And that's how quickly it can happen. Think about what you are doing and why you are doing it. But most importantly of all, are you going to be able to do it SAFELY?'

The last thing he said, much to my relief, was that since the loco had not actually moved, he was able to persuade the driver not to take the matter any further. For that I shall always be grateful, because he undoubtedly saved my railway career. After that, though, I became about as popular as a fart in a space suit at the shed. Most of the blokes totally ignored me, others made sarcastic remarks - 'We don't need any mincemeat today, thanks!' or 'They reckon that old Boris (not his real name) nearly lost a lot of weight the other day.' As a result, I was more than relieved when I received my call-up papers for National Service, as I knew that Battery Sergeant-Major Blake was a very kind and understanding man, who would always be prepared to listen to any complaint, no matter how trivial, and look after his men as if they were made of porcelain. NOT.

Army life was just the job for me and I enjoyed most of it, except for one Christmas Eve morning when Sergeant Major Blake came striding into the Signal Store and asked - 'Bombardier, have you ever seen Santa Clause flying over the chimney pots?' 'No Sir,' I answered, 'Never…' He gave a rasping chuckle, like a cockerel getting its neck stretched - 'You will tonight, boy - you're Guard Commander!' With that, he swept out cackling like an old crone. It's no wonder everybody loved him.

Army life was just the job for me and I enjoyed most of it, except for one Christmas Eve morning when Sergeant Major Blake came striding into the Signal Store and asked - 'Bombardier, have you ever seen Santa Clause flying over the chimney pots?' 'No Sir,' I answered, 'Never…' He gave a rasping chuckle, like a cockerel getting its neck stretched - 'You will tonight, boy - you're Guard Commander!' With that, he swept out cackling like an old crone. It's no wonder everybody loved him.

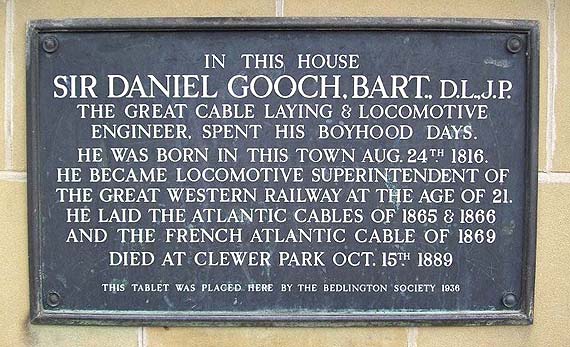

(Below) Everyone must know about the Bedlington Iron and Engine Works? If not, it may interest you to know it was where the first wrought iron railway line was made. Bedlington is the birthplace of the man who, for me, was the greatest locomotive designer that ever there was. Daniel Bart Gooch was his name, and at 23 years of age, he succeeded in putting right all the failings of Brunel's designs on the Great Western Railway. He collected speed records like Manchester United FC collect cups! I am, of course, biased…I live just a stones throw away. Goochies star was the Firefly series, and then he turned his hand at laying telephone lines. I'm proud to give the great man a mention on this page.

In the next part (below) I will tell you about my time at North Blyth where 'men were men' and the Company was glad of it. We were making that much money for the Railway (up to twelve per cent of the entire network income in 1963) that one night, over a few pints in the BRSA Club, a few of us decided to have a 'Unilateral Declaration of Independence' and keep all the money for ourselves! Alas, when the next day came, nobody could remember who'd been elected as President, so we put that plan on hold!

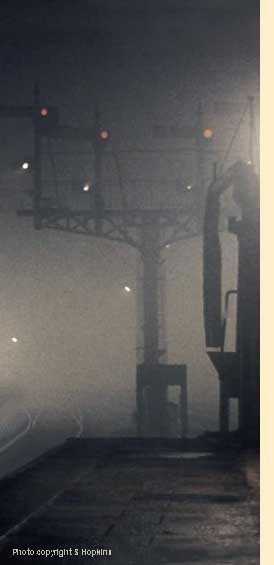

(Above-Below) These views of North Blyth coal stage and water tower are from Ernies excellent Photopic site link and shows a strange-looking 4MT 'kettle' well coaled up. (Below) A different view of the coal stage includes the chimneys of Blyth Power Station looming out of the mist in the distance. There was usually a couple of locos parked strategically beside the fence where two sleepers had been carefully loosened - they provided a well-concealed access for anyone acquiring coal from said locos for redeployment in home fires. All went well till some silly bugger pinched the sleepers too! They were replaced by immovable ones - and that put paid to the little adventure...

Following demob from the Army, and still a passed cleaner from my South Blyth days, I applied for one of the North Blyth firemen vacancies which appeared in BR's latest Vacancy List. Since my preferences were Blyth South or North, and Gateshead Depots, I waited with baited breath to see if anyone more senior had applied. Lo and behold, I received a notice telling me that I had been appointed to a fireman's vacancy, and told to report at North Blyth Loco the following Monday. I was chuffed to bits to get the job; it didn't matter that I had been doing firing duties during my spell at Blyth South before National Service, it was great getting back into doing a job I loved. On the Monday I duly presented myself at the sign-on window and embarked on another learning experience. The Foreman was a short chubby man with a mournful face and a thick drawling Geordie accent - 'Gan an hev aluek aboot th pleyus an aal see wats gannin earn,' he said, pointing out of the window.

I went out onto the pit where one of the labourers was damping a live fire down before shovelling it into a ballast wagon, and all the old familiar smells came flooding back; the acrid smoke, paraffin rags, hot oil and steam. I had a good look around the yard and found the fitters' hideout behind the coal stage - and, further up the Carriage and Wagon, found another bolthole used by the men - both handy places to hide when the Foreman was seeking someone to do a rotten job!

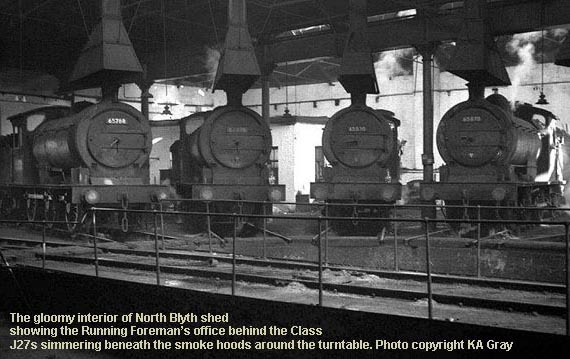

(Above) North Blyth shed was one of the dirtiest, smelliest places I have ever had my misfortune to be in, but it was home to lots of locos, so it didn't matter. What was more of a puzzlement to me over the years, was how some blokes could do an entire shift in this filthy environment and come out of it as pristine as they went in! Compared to them I was a proper 'muck magnet'. I'd arrive all spotlessly clean with sky blue overalls, polished boots and gleaming hat, but by the time I signed off you'd think I'd been sleeping in a smokebox! The shed's allocation of locos fared no better! Looking dirty and seemingly uncared for, Class K1 62024 awaits its next job at North Blyth on 18 July 1965.

(Below) Due to the Class K1s poor braking efficiency on loose-coupled heavy loads, they were poor performers on local mineral workings, and they never got much chance do their stuff on short heavy hauls, but on the longer runs they really came into their own, loping along without breaking sweat, but again, getting them to stop the load was the main cause for concern. And of course, with a load of empties, the temptation to play 'express trains' was too much for some drivers, resulting in one case of a derailment of around fourteen wagons at speed at Widdrington station and another case of a driver being clocked at 65mph on the Ashington-Lynemouth NCB Railway which carried a speed limit of only twenty! Another fine study of North Blyth Loco by Bill Wright showing Class K1 No 62067 sporting North Blyth and Newcastle stencilled lettering on the buffer beam on 31st October 1966.

FISHY GOINGS-ON AT NORTH BLYTH!

One day at North Blyth shed, a very unpleasant odour was detected in the Running Foreman's office, which, as time went by, escalated into the most disgusting stench and traumatized anyone who passed within twenty yards. Over the next few days, the comments raised began with a mildly inquisitive - 'Can you smell something?' to shocked outbursts of - 'Bloooody hell! It absolutely stinks!'

The office was scrubbed out with Jeyes Fluid, but even that couldn't mask the terrible stench, and so the running foreman abandoned the office and conducted business outside using a borrowed mess room table, and a telephone on an extension lead. Someone suggested that 'Big George' should spend a shift inside the office smoking his pipe because the fumes could paralyze cats from a range of sixty yards downwind, but it was reasoned that replacing one stench with another was not the way to resolve the problem. Eventually, after suffering this ghastly odour for eight days, the mystery was solved - somebody spotted an infestation of maggots wriggling on the floor under the foreman's desk - 'Bloody maggots!' the foreman said disbelievingly - 'Where the flaming June have they come from?'

He immediately ordered two cleaners to investigate - 'Leave no stone unturned,' he said.

As the two lads entered the office, they covered their mouths with rags - the putrid odour inside was unbearable. Then, awaiting the foreman's instructions, they prepared to turn the desk over, but before they could complete the task, there was a soft 'slopping' sound - and a rapidly decomposing carcass of a once-magnificent bass of around eight pounds in weight, fell onto the office floor covered by a seething, wriggling mass of maggots. Further investigation revealed a number of nails had been hammered into the underside of the desk where the rotting corpse had been secured.

Armed with this evidence the foreman mounted a full-scale investigation to find the culprit and ensure they'd be severely dealt with. Over the next two days, rumours were rife as to who it might be - and not surprisingly, the main suspect was myself. But then, in a small place like North Blyth everyone knew everybody's business, and it was common knowledge that I was a keen angler and a leading member of the  local Angling Club. Sure enough, I was one of the first to be called into the Shedmaster's office - and, being a very blunt Scot, he asked me point blank if I was to blame for incident, to which I replied - 'I would no sooner waste a fish in such a manner than I would set fire to a weeks wages, for that is how much the fish would have fetched on the quayside fish market.'

local Angling Club. Sure enough, I was one of the first to be called into the Shedmaster's office - and, being a very blunt Scot, he asked me point blank if I was to blame for incident, to which I replied - 'I would no sooner waste a fish in such a manner than I would set fire to a weeks wages, for that is how much the fish would have fetched on the quayside fish market.'

My explanation seemed to satisfy him because I never heard anything more about it. Even so, most of the blokes at the shed still suspected me. It wasn't until three weeks after the incident, that a young cleaner approached me in the BRSA Club. It was near to closing time, and he was obviously well served with booze. Slurring his words, he enquired how it was that I knew the value of the fish? He had heard the rumours flying around the shed that the bass might have been worth between ten and fifty pounds. I told him that I took the 'Fishing News' every week, which is the industry newspaper, and the price for Bass of the same size would have fetched between eleven and twelve quid.

At that, he gave out a discontented moan - 'Oh no!'

Spotting a confession heading my way, I quickly asked him who he would have shared it with?

'Danny!' he replied without thinking.

In an instant he'd dropped both himself and Danny in it, right up to their elbows!

(Below) The Ivatt 4MTs were in the same bracket as the K1 with regard to working mineral turns, and if anything the brake was worse because it did not release as quickly, which was imperative on a greasy rail as the loco began to slide (picked his wheels up) due to its vacuum operated steam brake taking just that little bit longer to create the vacuum to release it. The excellent 'Railway Archive' website provides a link to the MOT's report of a railway accident at West Sleekburn in Novemember 1959. (link) The accident was a direct result of 'wheels being picked up'. The two locos involved were J27's, one 'horsing' to get up the bank to Winning signal box, the other struggling to stop his load coming down from Marchey's House box. Can you imagine what it must have been like for the crew in the dark as both engines met head on? The Class B1 was also totally unsuited for hauling the heavy stuff around the Blyth and Tyne, and it was great credit to the men for adapting to working coal trains with semi-fast passenger engines rather than locos specifically designed for the job. But getting back to the Ivatt 4MTs, one of these engines, No 43000, was the best locomotive I ever worked on. It ran like a sewing machine, steamed on a nightlite and was without exaggeration a Rolls Royce of a locomotive. The rest were hopeless at the jobs we did. In this view below, No 43101 awaits its next job at North Blyth on 23rd April 1966.

I went straight into the Shed Relief Link at North Blyth, pairing up with a canny chap who had transferred from Hexham to Blyth after the shed there had closed. At the time, Beeching was closing Loco Depots like he was chasing a gold medal in a new Olympic sport, and thousands of displaced men had to find a new depot or accept a joke-book payoff of £350. The BR chairman certainly knew how to gain a railwayman's confidence and respect! My new mate and I were soon working like a team, if not exactly a dream team. The main part of the Relief Link involved stabling locos for the next crew, who prepared them for another six or seven hour stint hauling heavy coal. We stabled six locos per shift, first coaling and watering them, then moving them onto the pit to clean the fire, smoke box and ashpan. Then after replenishing the sandboxes, if the loco wasn't required immediately, it was moved into the roundhouse, turned on the table and put into a berth. Sometimes the next crew would be oiling and preparing the loco at the same time. This was because we were in 'bonus country' and the more jobs the road turns did, the more they got in their wage packets. The time allowed for stabling a loco was 80 minutes, but it could be done in 20 by good teamwork, and if you got your six done in short order, you were regarded as 'worked up' and had a short shift, sometimes getting off home in four hours or even less.

(Above) Back in the early Sixties, there never seemed to be enough money to go around. A top-money fireman was paid a meagre £6 17s 6d for 45 hrs hard graft, but the camaraderie was great and it helped a lot if you had a good mate. After I was promoted to the Road Link at North Blyth I was fortunate in having one of the best for 15 years, right up to the shed closing. Another great shot by Bill Wright of Class K1s Nos 62057 and 62059 at North Blyth shed on 23rd April 1966.

(Below) The Class K1 2-6-0s worked everything from light coal trains to express passenger services. Withdrawal of the class started in 1962, their final duties including the colliery trains previously worked by Class J26, J27 and J39 0-6-0s. The last K1 to be withdrawn was No 62005 in December 1967; the loco served as a temporary stationary boiler at the ICI North Tees Port Clarence Works in 1968 before being put into storage at Leeds Neville Hill shed pending a decision on its future. Now preserved by the North Eastern Locomotive Preservation Group, the loco is a regular visitor to preserved lines across the country. No 62005 is sporting Apple Green livery at Grosmont on the NYMR in June 1974. Click here to find out more about 62005 on the NELPG's excellent website.

FISTACUFFS AT NORTH BLYTH!

Let me tell you about the day I was working a Shed Relief Turn and one of the Road Turns had his last job cancelled at the last minute. The fireman had already got his fire ready for the next job and came down light engine from the sidings onto the pit, blowing off from both safety valves and belching smoke like Admiral Beatty's Flagship! My mate for that day went running over shouting - 'You've got to be bloody joking!' and in no time at all both men were snarling and spitting at each other, exchanging the most foul-mouthed insults I had ever heard, even in the army! I had no idea there was bad blood between them, but their tempers boiled over right before my eyes.

Now it should be pointed out that to qualify as a fireman you had to first progress through the Shed Relief Turn, therefore a passed fireman knew how much easier it was to clean a low burning fire than a raging firebox full of coal. Most fireman made every effort to run the fire down when an engine was homeward bound to the shed, so when my mate saw him bringing an engine onto the pit with a full firebox and boiler, he reckoned he had done the deed on purpose to get at him; the fireman told him he needed to visit a taxidermist and not to be so bone-headed. The upshot was that both men went over onto the beach, followed by a crowd of fitters and shed staff to watch the spectacle of both men sorting out their differences in time-honoured fashion - a punch up! Both men began battering each other to a standstill, both fell down, each feeling he had won the dispute when neither had, and they both ended up covered in bruises to no advantage to either of them.

(Below Left) Aerial shot of North Blyth shed showing the two empty lines emerging from beneath the two shopper lines on the North staith before fanning out into North Sidings. The eagle-eyed might spot the  chimneys on the shed roof indicating the circle of smoke hoods around the turntable. You had to pass the British Railways Staff Association Club (BRSA) on the way to North Blyth shed - a big temptation for some men! Arriving at the shed one night, I signed on at the window and said to the Duty Clerk in a jovial fashion - 'The Devil has put the temptation of the Demon Drink in my path Brother, but I have overcome Satan and hereby present myself for duty at the appointed hour.' The Duty Clerk, an extremely eloquent man, looked at me sadly and replied - 'Sod off!' So I did! This photo was purchased on eBay from www.all-youryesterdays.co.uk. It was taken by Whitley Bay photographer, Gladstone Adams, during a number of training exercises to develop reconnaissance skills for the Royal Flying Corps in World War One.

chimneys on the shed roof indicating the circle of smoke hoods around the turntable. You had to pass the British Railways Staff Association Club (BRSA) on the way to North Blyth shed - a big temptation for some men! Arriving at the shed one night, I signed on at the window and said to the Duty Clerk in a jovial fashion - 'The Devil has put the temptation of the Demon Drink in my path Brother, but I have overcome Satan and hereby present myself for duty at the appointed hour.' The Duty Clerk, an extremely eloquent man, looked at me sadly and replied - 'Sod off!' So I did! This photo was purchased on eBay from www.all-youryesterdays.co.uk. It was taken by Whitley Bay photographer, Gladstone Adams, during a number of training exercises to develop reconnaissance skills for the Royal Flying Corps in World War One.

Meanwhile, after the fight was over, I got on with cleaning the fire, coaling and watering the loco - which, incidentally, was one of the worst jobs I had ever done. I then handed it over to the next men who were waiting to prepare it, and as it was the sixth and last job, I had finished for day so I called in at the sign-on point and asked the Duty Clerk if he'd inform my mate that I'd be in the boozer. Half an hour later, I was gargling the dust and clinker out of my throat with pints of Black and Tan, when in came my mate, all sand and bruises from his punch up - 'Pint?' I asked.

'Aye, gan on then,' he replied.

'That's good, cus its yewer turn,' I said, 'So I'll have one as well…'

Then I saw what looked like a tear in his eyes - 'Hold on, your not crying are you?'

'Naar!' he answered - 'He poked his finger in me eye, that's all..'

Bloody liar I thought!

It was a few days after this episode that the fireman in question approached me to apologise for bringing such a bad job onto the pit. He said that he was about to offer to do the fire himself when my mate's big mouth entered the equasion; it was then he wished he had emptied the whole bunker into the firebox! I never did find out what their bad blood was over; the two of them had been at loggerheads for years. It probably started over something trivial, but instead of resolving it over a pint or two, they had allowed their dispute to fester until it escalated into undeclared war - but nearly every footplate man I ever knew carried on a vendetta of one sort or another, but more on that later…

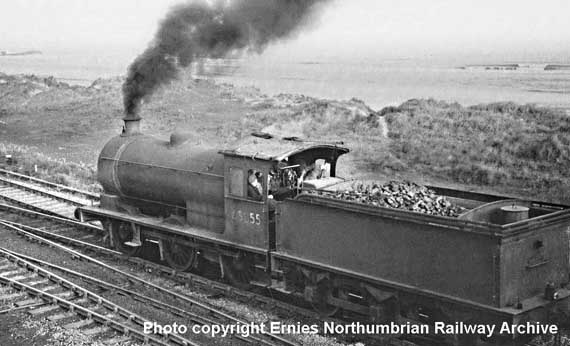

(Above) A general view of North Blyth Yard showing empty wagons being drawn off and two waiting to get in the empty line. Class J27 0-6-0 occupies the lines serving Hughes-Bolklow scrap merchants. Ernies Photopic site of the Northumbrian railway scene is a treat for blokes like me. I particularly like the photos of the staiths and the ships awaiting a loading berth; it's pure nostalgia. This panoramic view of the sidings at North Blyth taken from the footbridge is a true record, and when I visit the same place today it is hard to believe it was there - the hustle and bustle, thousands of tons of coal pouring into the waiting ships, locos arriving with a train of twenty or so 20 ton hoppers, and by the time the loco came around the train, the J77 had pulled half off in readiness for a clear run onto the staiths. Those were the days my friend - and I, for one, thought they would never end…but they did!

(Below) The Q6 was perfect for the jobs that we did, and it was the only class that was allocated to my mate and me. The engine was No 63362, which arrived ex-works from Darlington shining like a Grenadier's boots! When I told the wife the news, she said - 'Well don't think you're putting it in the back yard with the rest of your junk, I've got washing to hang out!' Click on photo to enlarge...

(Below) This photo shows Class J27 No 65819 standing outside No 2 road at South Blyth. The rusty patch on the smokebox was caused by a tiny hole that would draw air into the smokebox and set fire to the ash that accumulated inside. As the metal got hot, it distorted and let more air in and so the problem got worse until the metal would glow red - a spectacular sight in the dark, especially when the loco was working hard. What you'd see was the smokebox glowing like a big red blob and a column of sparks flying skywards. You often saw this happen on the Forth bank between Blaydon on the West Line, and at Central station when a loco was humping a load of oil tanks up there. My thanks to Bill Wright for his lovely photos.

After a couple of months, I got to know most of the men at the depot, and things were humming along nicely. It was hot, dirty work on the Shed Relief Link, but every now and then I'd be given one of the running jobs between the local collieries and the shipping yards at West, North and New Blyth. Sometimes I'd get the chance to work one of the Tyne Power Station jobs, which meant running on the 'real' railway through Newcastle Central Station with its monster bridges and forest of semaphores. Someone once told me that there were seventy-two signals on the east end alone, but I never got around to counting them! As time went by, though, more depots were closing and men from all over the country were being transferred to North Blyth. With so many senior men arriving on the scene we began to stagnate in the Shed Relief Link. Not that I minded much; the newcomers had to learn the road, which took time, and there was plenty of vacancies for us younger hands to get on the road jobs and earn more money.

CASANOVA JIMMY ON THE RUN!

I remember one chap called Jimmy (not his real name) who moved from Gosforth depot to North Blyth Loco to get away from them bloody 'lectriks!' he said.

Everybody called him the 'Professional Road Learner' because in the two years he spent at North Blyth he never once worked his own job. Not only did Jimmy lead a charmed existence at work, he was a charmer with the ladies too! At one point he was 'sweet hearting' two barmaids at the same time; they worked in different pubs on the main street in the town, which, in a small place like Blyth was a risky thing to contemplate.

However, he got his just desserts when he arranged to meet one of the lasses on her night off from the pub. As he walked into the bar at the agreed time, there she was, talking to his sweetheart number two, both girls no doubt discussing the odd coincidence that they were each dating a 'Top Link' train driver - Top Link? Jimmy liked to spin a yarn!

As soon as they saw Jimmy, the penny dropped with an almighty crash and the poor soul had to hightail it along the main street, with both ladies in hot pursuit, screaming obscenities. He managed to give them the slip down a side street, then made his way to the bus station to catch the bus home.

Alas, both ladies had out-manoeuvred him and arranged for the bus station to be 'staked out' by sweetheart number two's big brother - all 20 stone and nine foot six of him, according to Jimmy. Luckily, Jimmy spotted his would be assassin lying in wait and made a quick exit…deciding on discretion being the better part of valour and got a taxi home.

The following day, one driver was heard telling another that old Jimmy must be very popular with the ladies as he had seen two girls chasing after him in the town, both pleading with him to stop. Of course, this story got added to every time it was told, until Jimmy finished up being portrayed as a right Casanova. He basked in the glory for months afterwards!

It wasn't till years later that I got the full story from him; we were sitting in a pub in Newcastle and I nearly laughed my socks off!.

(Above) Wilson Worsdell's Class J27 (NER Class P3) 0-6-0 freight engine was derived from his earlier Class J26 (NER Class P2). Eighty locomotives were initially built in five batches in 1906-1909, their construction shared between Darlington Works, North British Locomotive Co, Beyer Peacock and Robert Stephenson & Co. A further batch of twenty fitted with Schmidt superheaters and piston valves was built at Darlington in 1920, followed by an additional order for ten at Darlington in 1922. This robust class was initially used for long distance mineral and freight traffic but they were gradually displaced by larger freight engines, and during their final years were more commonly to be found working in County Durham and south Northumberland on the short trip workings between the numerous local collieries and shipping staithes. With the onset of dieselisation gathering pace during the mid-Sixties, the Class J27 fell into rapid decline - the last member being withdrawn in 1967. Today, only one survives - a Sunderland engine, No 65894, which was purchased by the North Eastern Locomotive Preservation Group. Click here to visit the North Eastern Locomotive Preservation Group's site. In this view (below) Nos 65831 and 65832 await their fate at Sunderland Dock shed.

I SANG LIKE A SQUAWKING CROW!

After spending a good while in the Relief link, I eventually progressed into the Road link and got mated up with one of the younger drivers, a great 'all round' bloke and we made a perfect double act - not only on the footplate, but as a musical duo. He could play the harmonica like a professional and I, of course, could sing like a bird - or perhaps it sounded more like a squawking crow! Not that anyone could hear us above the beat of the engine and the clink-clank of side rods.

On one memorable occasion, though, our musical rendition in the cab was heard loud and clear! One balmy summer nightshift turn, we were working a long train of empty hoppers from the Tyne Power Stations, sailing along tender first without the backsheet down. As we passed Bedlington North Box, we were giving 'Mother Maghree' a good mangling, reaching the final crescendo of the song in fine style. But as we rounded the curve towards the overbridge, the distant signal went back to caution, then as we passed under the bridge the West Sleekburn's home signal went to red.

Stopping at the signal, I climbed down and went to the telephone, gave our train reporting number and destination, to which the signalman replied - 'Aye driver, the signalman at Bedlington North has been on the blower and wants you to examine your engine. He heard a terrible screeching noise as you passed his cabin!'

Thinking it was a wind up (born out of envy of our combined musical talent) I replied - 'Tell the Bedlington signalman to get stuffed! And tell him not to bother asking for any more coal for his fire because he's onto nowt!'

Unfortunately the Bedlington signalman reported me for using abusive language and I had a bit of a job explaining that one away!

(Below) No 65880 was the only superheated J27 at North Blyth. It never gave anyone a hard time. The loco was sweet as a nut to fire, and an excellent example of Worsdell's design.

LOST IN THE FOG AT WYLAM

During my regular mate's rest day, I signed on for a mineral turn at 19.20 with an ex-Percy Main driver called Jed (not his real name) who was a fair enough bloke, always ready with a joke or two - the sort of chap I'd call a 'Bright-side-looker'! The orders were engine and van to Lynemouth and a load to Stella South Power Station on the bank of the Tyne. The loco was 65880, a superheated J27 of good pedigree, and that suited me fine. We oiled him up and I piled a good back end into his firebox, so we could get another half ton of coal on the tender - Jed was an enthusiastic 'hard runner' and I didn't want to be trimming coal at two o'clock in the morning.

We collected the guard and brake van and set off to start the longest shift I have ever worked! Everything went like clockwork to begin with. We had a spectacular run up the bank between Seghill and Earsdon - the column of fire blasting from the chimney must have been visible from outer space! We had three quarters of a gauge glass and all looked in order, until we were put inside at Little Benton, a holding siding for Heaton South Yard, where two trains were already waiting - the Aberdeen fish, and an Edinburgh-Leeds Parcels. I went to the signal box, signed the train register and joined the two Scottish lads enquiring about the delay. The signalman told us there was thick fog south of Newcastle and two points failures in Central station.

I had a good creagh (talk) with my Caledonian brothers and their story north of the border seemed to be the same all over the railway, with depots closing and hundreds of displaced men flooding the few remaining sheds, effectively reducing the number of promotions to driver status. It was all doom and gloom in the signal box until 'Call Attention' came on the bells. After speaking on the phone the signalman said - 'The two fasts will go first.' Another flurry of bell 'ding-ding-dingdingdings' sounded and the bobby said - 'Right lads, its fish first then parcels.' Then, addressing me, added dolefully - 'As for the slow…it's when we can, and if we can.'

I walked dejectedly back to 65880 and informed Jed, who was devastated by the news; he had planned on being tucked up in bed by 02.00 - 'Them twerps think they can run the job!' he raged - 'They couldn't organize a paper round between them!'

I sat quietly, listening to his tirade, and hoping to cheer him up, said jokingly - 'Well at least it isn't raining!'

Jed just glared at me, and I knew I'd gone too far. Without saying another word, he dismounted the loco and went storming off to the signal box muttering obscenities under his breath - 'Raining, effing raining, is that supposed to be effing funny, or what?'

Whilst Jed was stamping up the steps to the signal box, Willy, our guard arrived to find out what was happening. I put him in the picture, and then enlightened him on Jed's mood - 'Look, when he comes back, whatever you do…don't mention rain!'

We watched Jed waving his arms about in the box, and then he picked up the phone, shouted more 'f'-expletives, before slamming the receiver down and making his way back to the loco. He climbed up and plonked himself down - 'We can't get through the town because there's only two roads for all traffic, and there's thick fog southwards.'

Willy winked at me and said to Jed - 'Aye, and I've heard there's a forecast for heavy rain as well.'

I looked at Jed and Jed looked at me and we all started laughing together.

The crew of Class J27 No 65855 are waiting at North Blyth sidings for the guards van to be gravitated from the rear of a delivered train prior to shunting it into the van line, and then picking up another load of empties for the next trip to one of the local collieries. The rocks on the beach at the top right are called the Rockers and just visible higher up is the Power station cooling water outfall.

We were inside at Little Benton for just over two hours, but managed to keep our spirits up with a hot brew and a joke-telling competition. It wasn't until the signalman came to his window and shouted - 'Are youse buggers going or not?' - that anyone noticed we'd been given the signal to start.

With all expectations raised, we set off, but within ten minutes we were back inside on the refuge at Heaton. We were halfway down the road when we got a green for the Tynemouth, so we trundled sedately through the junction and then through Heaton station, before coasting across Byker viaduct, through Manors platform and then came to a stand at the signal controlling the road into Central station. I climbed down and went to the signal post phone, but before I could pick it up, Jed shouted - 'Okay Freddy, its off.'

With just a breath of steam, we ghosted over the junction and moved quietly down Platform Ten where a crowd of mournful passengers gathered expectantly at the platform edge, but then turned away dejectedly when they saw our smelly old 65880 approaching with a train of coal trucks.

We were stopped again at the platform end, I jumped down and spoke on the phone to the signalman, who wanted to know if we'd go via the Forth Bank, I yelled at Jed - 'Forth?'

Jed gave a thumbs-up sign. I informed the signalman and the signal came off with the 'F' route indication. So away we went again, only this time moving cautiously onto the bank, knowing the guard would be trailing his brake on to aid us with the load. We encountered a lot of mist as we dropped down the bank and Jed remarked on how it was getting a great deal colder.

The time was approaching 01.15.

At the Forth box we saw that both the starter and distant off, so Jed allowed the speed to rise to thirty as the load kept pushing us down the bank. We were about half way to Elswick Works (site of the famous Vickers firm) when we found ourselves enveloped in thick fog - and a very chilly one at that.

'Keep a good look out, Waggy lad!' Jed shouted…

As if I needed telling! Long before the introduction of AWS or colour light searchlight signals to help train crews, there was just one little flickering paraffin lamp behind a bulbous glass bull's-eye magnifier, and on this particular night the thick fog covered everything like a shroud. The way it smoked in the autumn night was uncanny - one minute it was clear and fifty yards on it was a pea-souper - or, as my fisherman friends would say - 'Tar Thick, enough to stretch your eyeballs two feet!' It wasn't until we crossed the Tyne before Blaydon Yard that I had any idea of our whereabouts, but no Blaydon Races this night! We crept through Blaydon station with the fog swirling around, stroking our faces like icy fingers, even inside the cab.

'Aye, that's us in!' cried Jed, spotting the direction signal for the Power Station yard… and so in we went, gingerly feeling our way. We stopped at the end of the reception road, fastened the load up with the lever hand brakes, ran around the train and kept an eye out for the guard.

Willy came to the loco and informed us that Control wanted us to go to the ICI Plant at Prudhoe and take thirty empty hopper wagons to Ashington.

I burst out laughing - 'Oh, that's got to be the best joke of the night, Willy. It looks like you've won the competition!'

'It's no joke,' he replied - 'But I said I'd ask you.'

Jed scratched his coconut, deep in thought, and then said - 'We can either knock Control back and go home, or we can do this ICI job and wring its neck for as much overtime we can get.' We decided on the latter and to make it pay…lots!

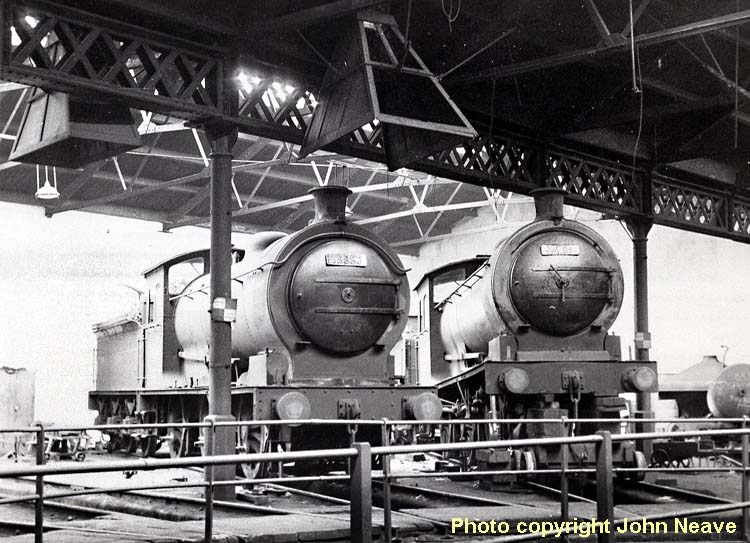

(Above) John Neave's shot of J27s at North Blyth shed on 1st August 1965 shows No 65851 on the left with missing smokebox door handles and no shed number plate… I wonder who took those away? They did at least have the decency to leave the bolts! On the right, the super-heated J27 No 65880 is jacked up on blocks enabling fitters to examine the wheels. Click here to visit John Neave's excellent Flickr photostream containing over 4,000 photos - including several sets of BR steam and diesels from the 1960s to the present day. During our exchange of emails, John says he visited the shed on many occassions when he stayed with his Aunt at Monkseaton. John's two shots on this page are the best I've seen inside the roundhouse...

With the fog thickening over the Power Station yard, we picked up the van, and moved up to the signal for the platform, but the choking fog was even thicker there and we almost passed it. The Blaydon signalman told Willy he had three to come before we could go, so we climbed into the guards van to keep his fire company.

We heard the first two go past, but didn't see them. Then the last one passed, showing a faint glow from the firebox. We returned to 5880, waited for the signal to clear us into the platform, and then crossed on to the up main, stopping behind the starter. After it cleared we set off for Prudhoe ICI, tender leading, at no more than fifteen miles per hour, with the fog chilling us to the bone and stinging our eyes, making the tears run. Jed was familiar with the route, so he saw the signals long before me, but caution is the name of the game in these conditions, and it took a long time to travel the relatively short distance to Prudhoe. As we got closer, Jed slowed to a walking pace and then stopped at the home signal, which was on. I went to the phone and spoke to the signalman, who informed me that he would clear the signal, but as the ICI was already occupied by another loco waiting to get out, he wanted us to reverse into his short siding and clear the main line as there was traffic due.

Jed took us into the short refuge siding, and then climbed down to speak with the signalman. Meanwhile I dropped a few scoops of coal just over the fire hole door, pulled the door open and tried to warm myself. A few minutes later, Jed returned in a buoyant mood! Having decided to choke the job for as much overtime as possible, the situation was playing right into our hands…and so the more delay the better! The signalman had told him he didn't know how long we'd be delayed, but said he'd give us a shout on his megaphone when he was ready for us.

The time was 03.00hrs.

We decided to drop the back sheet, which consisted of a tarpaulin sheet fastened to the edge of the cab roof and tied back to brackets on the tender top. It made the cab marginally more comfortable and we settled down to wait a call from the signalman. Jed had a thermos flask the size of an Eddystone Lighthouse, and after a mug of hot tea and a quick bite, I rolled up my reefer coat, using it like a pillow, and lay down on the seat with my feet on the tank wing and dozed off. An hour later, I was awoken by the sound of Jed shovelling a few lumps of coal into the firebox. I stood to my feet, but my legs were ice cold, as if they had been in the freezer for an hour. The damp fog had numbed my legs from the knees down, and I was barely able to move, let alone climb down to have a Jimmy Riddle; at that point I would have cheerfully put both feet in the firebox to get warm again.

The time was now 05.10hrs.

(Above) Another great interior shot of North Blyth shed by John Neave. It shows a pair of Class Q6s Nos 63413 and 63429 flanking a Class J27 No 65858 on 1st August 1965.

The lockers in the background remind me of a spectacular mishap that happened during a shed relief turn. The men were stabling a Q6, first disposing of the fire, then cleaning out the ashpan and smokebox, before moving the loco quietly into the shed. They positioned the Q6 on the turntable, getting a good balance first time, and then turned the loco in alignment with a vacant stall.

The driver climbed into the cab and tried to move the loco backwards, but the Q6 didn't want to go, so he applied a bit more steam - and all of a sudden, before he could stop it, the loco shot off the table, bounced over the stop chocks and rammed the tender through the shed wall! It destroyed several lockers where the men kept their equipment, and created a hole big enough to drive a double decker bus through!

Needless to say, everybody in the shed ran to see what all the noise was about, found the shed shrouded in dust and a 44-ton tender wedged in the wall...

Fortunately, the driver wasn't injured, but he was obviously shaken up and adamant that he had applied the brake as soon as the machine started to move, but to no avail. The loco was unstoppable!

As it turned out, the Q6's boiler was too full, so instead of steam getting into the steam chest, it was pressurized water. I've seen quite a lot of videos with locos priming - or 'catching their water' as we used to call it in the old days. When this occurs, there is a very real risk of causing serious damage to the engine's motion. That's because water cannot be compressed and therefore it cannot escape from the cylinder as readily as spent steam.

The consequences of engines catching their water can lead to bent connecting rods/side rods and even blown cylinder covers, accompanied by a deep roaring exhaust, even water showing in the exhaust at the chimney. Click here to visit John Neave's excellent 'Going Loco' website.

The fog continued to swirl around us, and it wasn't until a Q6 came barking past with a load of empty hoppers that Jed guessed it was our turn next. Sure enough, a booming voice echoed through the fog -  'Come on, 5880… Wakey- wakey!' shouted the signalman on his megaphone.

'Come on, 5880… Wakey- wakey!' shouted the signalman on his megaphone.

We moved off into the fog, stopping at every hand point to make sure they weren't half-cocked. The load was on four road, so we dropped the van on the back then returned up two road and coupled on at the other end. Willy arrived with the train details - twenty-nine empty hoppers, no shoppers to shunt out, and ready to go. Some hope!

Jed asked me to inform the signalman that we were ready on the signal phone, which I was happy to do, but by now the fog had become so thick on the ground that within a few yards of leaving the footplate I felt totally disorientated in the pitch black. Not only had I lost sight of the engine, I had lost all sense of direction and I only managed to find the phone by groping along the perimeter fence. Alas, the phone wasn't working, which meant I'd have to go to the signalbox and tell the bobby personally.

Stepping carefully over lumps of rail strategically placed to injure careless feet, I headed towards the signalbox, but the fog seemed to drape around me like a blanket and although I had a mental picture of my surroundings, I couldn't shake off the feeling that with every step I took, my sense of direction was seriously flawed. I had misjudged the distance badly and knew I was hopelessly lost. Then, to cap it all, I heard the whistle of an approaching train!...

It was my worst nightmare; I had no time to dawdle. I knew which direction the train was coming and tried to gather my wits, but it wasn't easy in the middle of a pea-soup thick fog at the dead of night - I could've been standing in the middle of the main line for all I knew, so I reached down and touched the rail nearest to me and my worst fears were confirmed - I picked up a definite vibration…

All at once my predicament called for desperate measures, I had to make a decision fast. I was standing in the path of an oncoming train and made a move to lie down in the six-foot! It was all I could think of at the time, a split-second decision, probably reckless, irrational, but the six-foot was the best place to be in the circumstances. I lay face down, clutching the ground for dear life, listening to the beat of the loco getting louder and louder, and then an almighty rush of noise drowned everything as he roared past me less than four yards away, whipping up the ice-cold fog across the ballast - and then just as quickly, it was gone…

I staggered to my feet, shaking like a leaf - both from cold and shock. Then I heard a signal arm 'clank' down somewhere in the distance and immediately headed towards it. I located the signal post phone, told the bobby we were ready and then made my way back the same way I came, first reaching the boundary fence, then retracing my steps back to 5880. I climbed into the cab, where an aggrieved Jed was waiting - 'Where the bloody 'ell have you been?' he said accusingly.

When I told him the story, he looked at me blankly, and said - 'Did the signalman say how long we'd be?

'No,' I replied.

'Then you'd best go back and ask him.'

'You can go and ++++ yourself!' I replied, and we both had a good laugh.

We finally got away at 09.20hrs, first stopping to fill the tank at Blaydon, where I asked the signalman to arrange with Control for food rations at Central Station. A half hour later, we ran into platform eight where one of the platform lads was waiting with a cardboard plate containing two butterfly cakes and two small bottles of coke. Jed hit the roof! - and not for the first time that night he stormed off cursing and swearing, this time in the direction of the Station Master's bolthole. He returned twenty minutes later with four bacon sarnnies, a full flask and a pocketful of tea bags. He had also arranged with East End cabin to put us inside at Heaton North Yard, where we spent the next fifteen minutes devouring the sarnies, washed down with mugs of tea strong enough to take paint off. We eventually signed off at 12.47hrs and got paid an extra shift because we couldn't get back to work until our twelve hours rest had elapsed by the following daytime.

As Jed said - 'That's the way to do it!'

POTTED HISTORY OF THE PORT OF BLYTH

(Below) The coal shipments to the London Power stations consisted mainly of very small coal known as 'slack', a term that is all but forgotten in today's modern society. For example, I recently showed my granddaughter a lump of coal and she didn't know what it was! So, for the benefit of younger readers, David has asked me to don my thinking cap and explain a little about the history of Blyth, which at its height was the largest coal exporting port in Europe. This shot below shows two Baltic Topsail Schooners at the quayside before the New and Old Blyth staiths were built. I had to print this picture to appreciate how good it really is. It must have been taken with a plate camera - the detail is superb.

(Above) This historical view looking upstream towards the West Basin was taken long before the staith was built. In bygone days the sailing ships were loaded alongside the jetty by barrows and chaldrons that were run in sets along wooden rail lines from the outlying collieries. Before coal, however, the main export was salt. This was derived from seawater boiled off in great pans, leaving the residue of salt at the bottom. The pans were fired by sea coal gathered from the beach. I lived at North Blyth for twenty years and never bought a nugget of coal in all that time! If there was nothing to be found on the beach there was always the hole in the fence at North Blyth shed! The backside of the North staith was called the Pan Sands, though I don't recall it being very sandy when I was there...mostly mud!

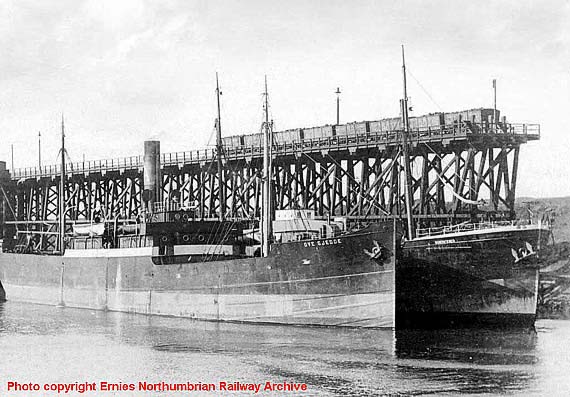

(Below) Fast-forward eighty-odd years and this view of five vessels awaiting a berth at the staiths clearly illustrates how both shipping and the Port of Blyth has developed. The first coaling staiths were opened in 1867 at the north side where sufficient depth was dredged in the river to allow berthing facilities for ships of over 1,200 tons. By 1881, the Blyth Harbour Commissioners, in conjunction with the North Eastern Railway, constructed two coaling staiths at the south side, followed by a further two staiths in 1888. Sixteen years later the harbour was enlarged and deepened, and the NER constructed an additional set of staiths on the north side of the river for the shipment of coal originating from collieries in Ashington and Bedlington areas.

(Above) This aerial photo might help you identify the location of some photos on this page - amongst other things it shows the Bates Loader, the West and North staiths and the Chain Ferry crossing the river. The white building marked 'Pots' is actually a pub called the Golden Fleece nicknamed the 'Flood' - on the spring tide it was rather disconcerting to be standing at the bar and feeling the North Sea lapping around your ankles. It paid to wear wellies! The small white building on the landside of the two ships tied up opposite the West Staith is the Ridley Arms, otherwise known as The Willick. It was the best pub in the world: motto -'We Never Close'! Even the local Bobby used to drink there. The two lines of houses between the West Basin and the beach are Miners houses named Boathouse Terrace, and the short row was called Boca Chica - and, before you ask, I haven't a clue! The single ship opposite Bates is being broken up at the Hughes Bolkow's ship breakers.

(Below) Another superb aerial shot from the David Barlow collection, this time looking across the harbour towards Blyth. I've marked the location of Blyth station (closed 12th August 1964) and South shed. The Gasworks was situated next to the Old Blyth sidings, which was a strange location in my view - whenever the pilot was shoving a heavy load of hoppers onto the staith the sparks would be 'pinging' off the top of the Gasometers and showering the ground around them like a Roman Candle, yet nobody seemed in the least bit concerned! I've arrowed various points of interest on the opposite bank, including the Dry Dock, Shipyard and the two Graving Docks - the latter used for painting ships' bottoms! Special compounds were used to stop the weeds and barnacles growing on the hull, some of it was toxic, so specialists did the job. The Pan Sands is where some of the saltpans were located. The Cowpen and Cambois Colliery sidings (C & C Railway) fed the two loaders a little way downstream - the loaders can be seen in the next aerial photo below.

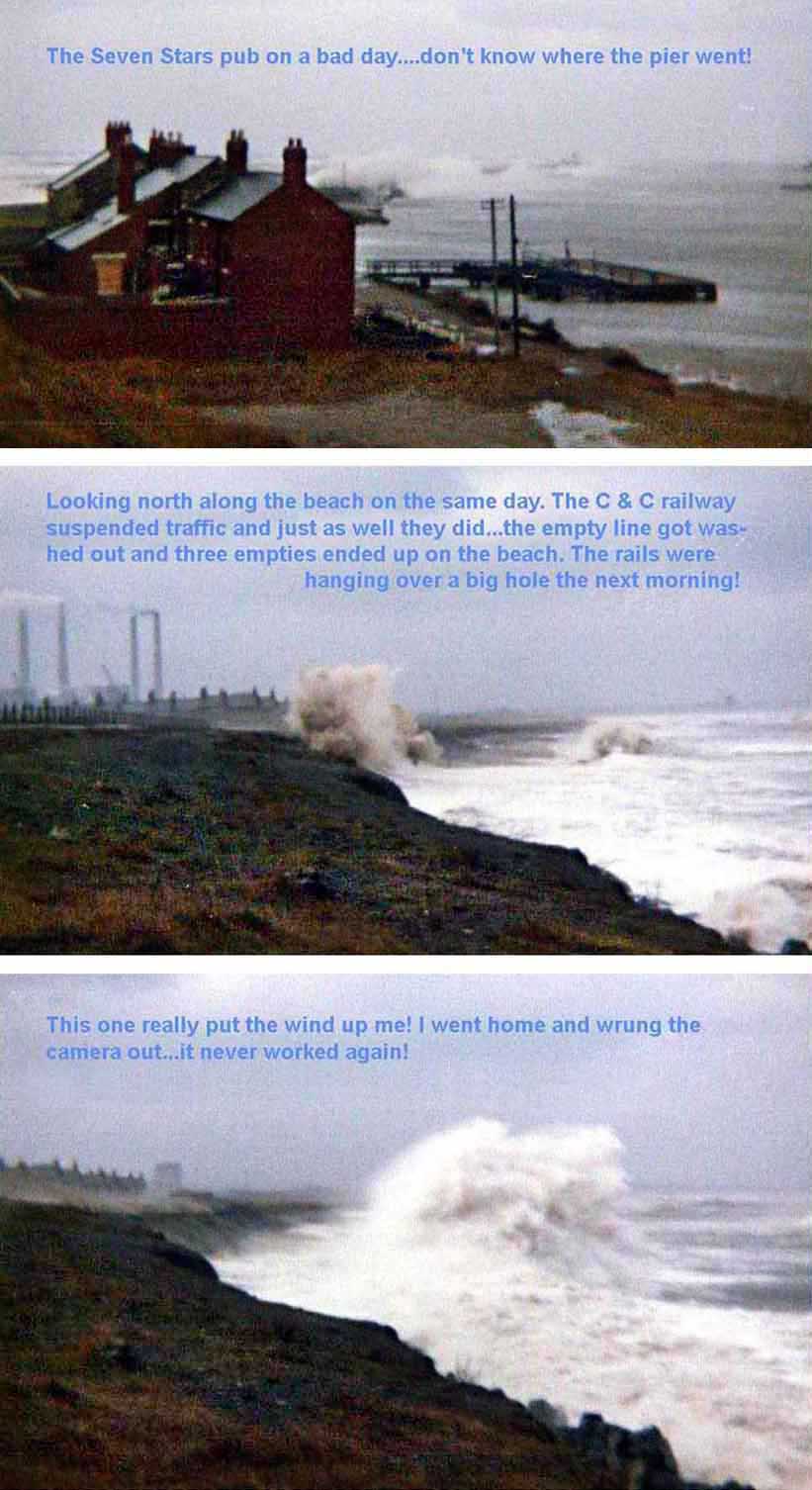

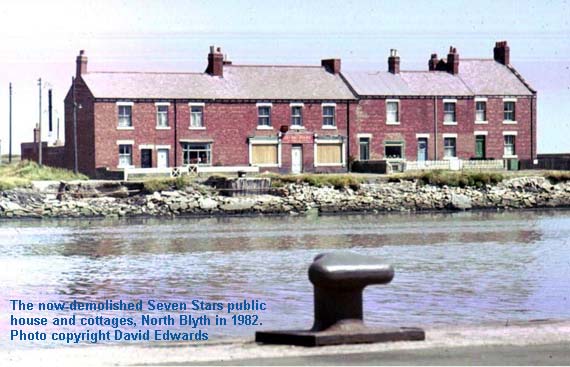

(Above-Below) This shot was taken in the mid-1950s before the Power Station was built. The 'Seven Stars' pub can be seen on the right. This pub had no electricity and only bottled gas, but it had a roaring fire in the winter months, and was illuminated by paraffin lamps with long fluted glass chimneys and brass reflectors. The pub had the best sounding piano for miles around. The dray lorry delivered the booze via the Pan Sands, and often got stuck - the draymen had to wait in the pub until the tow truck could get the lorry out. On one occasion the tide came in and the poor souls were marooned in the pub for twelve hours. I wanted to take them some sandwiches, but our lass wouldn't allow it! (Inset) If you needed any evidence of rough seas, this is it!...I ventured out to record the scene with a camera - one wave scared the living daylights out of me.

(Below) At its peak there were five sets of staiths built by the North Eastern Railway and its successor the London North Eastern Railway (LNER). The staiths consisted of a timber trestle where the line climbed from exchange sidings to a height above the waiting ships, enabling coal to be gravity loaded by Teeming Gangs directly into the ships' holds. The trackwork on the staiths was built on a slight incline, enabling the 'rider on' to gravitate the load down to the spout heads, where the bottom doors of the hoppers were opened and the coal went down the shutes into the hold of the ship below. After the wagons were emptied, another 'rider on' gravitated them down the empty line - and, if his luck was in, an engine would be waiting for a load and the guard would take the empties off him. If not, he had to take them all the way down and secure them, before walking back to the top deck to wait for the next lot. The trackwork on the staiths also included several crossovers to facilitate the shunting of wagons.

(Above-Below) Brass Monkey weather! You can almost feel the bitter cold in these two shots! The wind and rain sweeping in from the North Sea reduced the temperature at Blyth to well below freezing.

When I asked Freddy if he had any comments to make about the wintry conditions, he replied - 'The bloke in the snow will surely be a teemer, probably chucked out of the cabin for farting. This was seriously frowned upon at break time...and rightly so!'

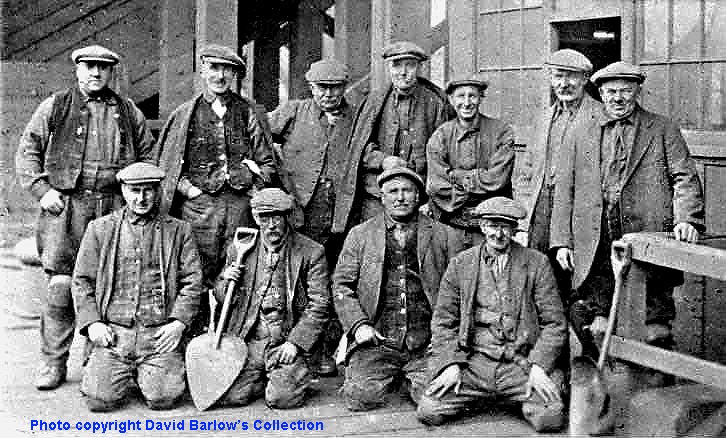

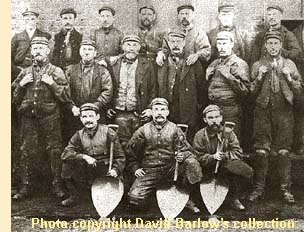

The teemers were employed on the top deck of the staiths, and consisted of a corps of five or six men, whose job it was to take charge of the twenty-ton hoppers brought up by the pilot engine for unloading. The teemers were the highest paid men on the railway, receiving sixpence per ton of coal they shipped - 6d equates to 2½ p in today's money, which doesn't sound a lot, but on a good day they could load anything between eight and ten thousand tons.

The wheel on the right of the photo (top) is part of the gear for positioning the shute to ensure that the load is as level and tight packed as possible to prevent it shifting in a seaway thereby making the vessel unstable.

The artic conditions reminds Freddy about the member of the teeming gang, who climbed into a wagon and started jumping up and down in a bid to release the freezing coal. When the coal dropped, so did he! He went straight through the wagon's bottom doors down the spout into the ship. One of his mates leaned over the rail, saw he was okay and shouted - 'Ho, you can't go home yet, there's another seven wagons to do!' You can imagine the reply...

(Below) Hundreds of men were employed at the Port of Blyth, including gangs of Trimmers, who played a major role the port's prosperity. These men worked hand in glove with the Teeming Gangs to ensure the coal was loaded evenly in the hold of the ship; it was essential to pack the coal tightly so that it would not move in a seaway and destabilize the vessel. The teemers positioned the spouts to distribute the coal where the trimmers wanted it, since this saved time in packing the coal into the corners of the hold. In a busy port like Blyth, time was money and the more efficiently the men got the job done, the quicker they could move onto the next one - 'More coal in the hold, more money in the pocket' - was the motto…

(Right) The final job in loading the coal was very much 'hands on' for the trimmers, who crouched on their knees inside the hold of the ship and began sweeping the coal behind them into the corners using their  custom made heart-shaped shovels - this 'paddling' action was similar to paddling a canoe. After making sure the coal was levelled off at the top, the skipper, or first mate checked the hold hatches fitted snugly before the ship was winched along the jetty and the next hold was aligned beneath the spout to receive a further payload.

custom made heart-shaped shovels - this 'paddling' action was similar to paddling a canoe. After making sure the coal was levelled off at the top, the skipper, or first mate checked the hold hatches fitted snugly before the ship was winched along the jetty and the next hold was aligned beneath the spout to receive a further payload.

(Below) Although employed as a railwayman, I was just as interested in Blyth's maritime shennaigans! I remember one morning when the beach was covered with scaffolding planks as far as the eye could see! The jetsam was the result of deck cargo shifting on a Norwegian ship, and the whole lot had to be jettisoned otherwise the vessel would have rolled over. They say it's an ill wind that blows no good, but it was great news for the villagers who spent the next two days dragging 20ft planks from the beach and stowing them in whatever place they could find. In the normal way, any property found at sea is divided into Flotsam - that is, cargo floating after falling off a maritime vessel accidentally, or Jetsam - when the property is found after being jettisoned to lighten the load of a ship. Then there's Lagan - meaning if it lies on the seabed and is recoverable at low tide, and Derelict - that's any cargo unwillingly parted with at sea. But under any name, the arrival of 20ft planks provided a bumper pay day for the villagers!

(Above) Shipbuilding at Blyth rose to an impressive level during the early part of the 20th century. The Blyth Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company had five dry docks and four building slipways, which made it one of the largest shipbuilding yards on the North East coast of England. During the 1st and 2nd World Wars, the Blyth shipyards built numerous ships for the Admiralty including the first aircraft carrier, HMS Ark Royal. Shipbuilding continued at Blyth until the yard was closed in 1967. In this shot 'Pulborough' is launched from the Blyth DD & SB Ltd slipway in April 1965. Stephenson Clarke Shipping Ltd owned the vessel before it was broken up in 1986. For more information on Blyth's shipbuilding history click here to visit the excellent 'Communities Northumberland.gov.uk' website...

(Below) The launch photo (above) reminds Freddy of the tale about a ship being launched in spectacular fashion from the DD & SB Ltd shipyard at Blyth. The story goes that half of the drag chains had not been tied on! As a result, the ship came racing down the slip, shot across the river and crashed into the staiths on the opposite bank. It hit the pilings just below the point where the driver of a J77 pilot engine had stopped on the top deck to enjoy a grandstand view of the launch. The impact on the staithes says a lot for the strength and flexibility of the wooden structure, for the boys on the engine said the top deck swayed a good seven feet one way and back again, but surprisingly it remained in one piece. However, the shocked driver wasn't taking any chances - fearing the whole lot was going to collapse like a pack of cards, he slammed open the big valve and the J77 shot off the staiths at 60 mph! Happily, both J77 and the crew survived the impact - though rumour has it the fireman had to dash off home to get some clean breeks on! His mammy said he even had to change his socks! This is the damage the ship did!...the structure has been tidied up a bit in readiness for the joiners to start repair work. Note the temporary repair to the walkway in front of the cabin where the rudder destroyed it.

(Above) This view looking upstream towards the West Basin shows the Chain Ferry pulling itself on wires across the river between Blyth and North Blyth. The wires had to be dropped to the bottom of the river when a ship was going up to the West Staith or Bates…it all sounds a bit dodgy in practise, but no mishaps were ever reported.

(Above) This view looking upstream towards the West Basin shows the Chain Ferry pulling itself on wires across the river between Blyth and North Blyth. The wires had to be dropped to the bottom of the river when a ship was going up to the West Staith or Bates…it all sounds a bit dodgy in practise, but no mishaps were ever reported.

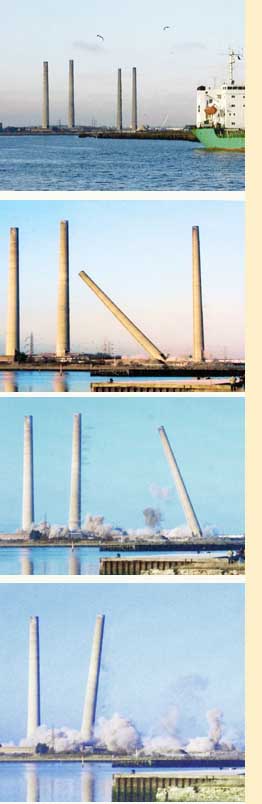

This view shows the twin chimneys of Blyth Power Station dominating the horizon. Construction of the second station began in December 1961 shortly after the first station became fully operational in June 1960. The stations were built during a period in which there were great advances in power station technology, and their combined capacity of 1,730 MW in September 1966 made Blyth Power Stations the largest electricity generation site in England - albeit briefly; Ferrybridge C Power Station took the honour when it became fully operation later that year. The Blyth stations generated enough electricity to power 300,000 homes. Click here to visit Wikipedia.org's comprehensive page on the Blyth Power Station.

(Inset Left) Last stand for Blyth Power Station's cimneys. You can see the smaller shots going off up the right side of the chumneys to split them open a millisecond before the main shots take their legs off. No photograph can do justice nor capture the emotion of the moment it generated when the giants died. Photo courtesy Bob (Radio Bobby) Brown.

(Below) Another view looking upstream, this time showing the huge bulk of the North staith's timbers and the 'B' Power Station under construction in the distance. When finished the four large chimneys of the coal-fired Blyth power stations - also known as Cambois Power Station - became a familiar landmark for miles around over the next forty-odd years. The 'A' Station's two chimneys each stood at 460 ft while the 'B' Station's chimneys were taller, at 560 ft each. The stations were built alongside each other on the northern bank of the River Blyth between its tidal estuary and the North Sea. After the station ceased to generate electricity on 31 January 2001, both 'A' and 'B' stations were demolished - the stations' chimneys being the last to go on 7th December 2003. Click here to visit Jason Thompson's photo gallery of the chimneys being felled. Another familiar Blyth landmark is the curious-shaped Bates Loader on the left (see next photo below).

(Below) Close up view of the Bates Loader showing the damaged top of the jetty caused by a collision with SS Cormist in a westerly gale.