THE 'GENERATION GAP'

Introduction by David Hey

Although Fred Wagstaff is a few years older than me, the difference in our ages means little or nothing nowadays, but back in the 1950s the gap then was huge; whilst Fred was doing his National Service I was still running around in short pants collecting engine numbers.

The Fifties was a decade of 'make-do-and-mend' and most young kids were grateful for the little they had - which on the face of it, wasn't a lot - and as for career prospects? Well, those of us with a passion for steam trains wanted to be an engine driver, pure and simple...it was every boy's dream.

But all too quickly you grow into adulthood and your expectations are raised a notch higher. Gone are the innocent days of childhood; looking around you see all the material things that others have - things that you don't have yourself - and the starry-eyed notions you once had of being an engine driver begin to take on a whole new meaning. You want to make as much money as possible which means raising the bar even higher.

Then before you know it, you meet a girl and in no time at all you're married with 2.5 kids, mortgaged up to the eyeballs and sinking beneath a mountain of debt, followed by a mid-life crisis and stuck in a job that you hate doing, and by the time you've reached retirement age, it suddenly dawns on you that no matter what you set out in life to achieve it was never enough...

you're married with 2.5 kids, mortgaged up to the eyeballs and sinking beneath a mountain of debt, followed by a mid-life crisis and stuck in a job that you hate doing, and by the time you've reached retirement age, it suddenly dawns on you that no matter what you set out in life to achieve it was never enough...

Good grief, this is depressing stuff! A live wire like Freddy will firmly disapprove!

What I'm really trying to say is that today's kids have the same hopes and desires that we had at their age, but unlike the role models we aspired to emulate, there's no one comparable today.

Youngsters no longer aspire to be engine drivers; they dream of being pop stars with a smash No 1 album, glossy-mag photo shoots and excessive media scrutiny, all of which is a load of cobblers!

The abnormal amount of hero worship being lavished on today's celebrity culture is nothing short of mortifying. It only serves to trivialise the more important things in life.

That's why I've loved working with Fred. For if anyone deserves my hero worship it is the countless thousands of railaymen who did a hard, dirty job and in filty conditions, whereas the rest of us were aspiring for bigger and better things elsewhere...but do you know what? No matter what we have achieved in life, at the end of the day we all end up the same - a pile of ashes or six feet under.

Right! Enough said...during the time Fred and I have been putting together his 'Footplate Stories', he's revealed himself to be a quintessentially eccentric northern bloke, who doesn't fanny about with airs and graces, and whose wicked sense of humour makes a refreshing change from the risible PC culture we live in today. For example, just two weeks after starting on his stories, he told me - 'D'ya know what, Davey?' he said, somewhat surprised - 'I've got to thank you for getting me involved in this writing lark, I didn't think I would enjoy it so much, but I am! I feel that I've been very lucky all my life and have just about achieved everything that I've set out to do. The only thing that I didn't accomplish involved Pans People and the Three Degrees and some of the most depraved and unspeakable activities it is possible to imagine!'

See what I mean? - PC it most certainly is not, but then compared to the lack of manners, humanity, dignity, honour and respect that we see in today's unforgiving society, Fred's outspokenness is oddly reassuring. Quite simply, he tells it as it is - Fred is a fine example to us all.

But I'll let Fred take up the story…

(Above) This is the boilersmiths corner inside the roundhouse at North Blyth, and my guess is that No 65801 is having trouble with leaky boiler tubes in the smokebox. The procedure in this case would be to allow the boiler to go cold, and then insert the tube expander, which consisted of three rollers, which rotated on a conical head, and as the core was rotated it pulled the cone in and gradually the pressure tightened the tube in the smokebox boiler plate, then when the loco was fired up and everything got hot, the metal expanded, and hopefully the leak would take up.

This photo reminds me of my old days at Blyth, where a neighbourly spirit prevailed and everyone in the community was willing to help one another for next to nothing, or the favour might be returned in kind that ultimately benefited all. So when I needed to replace the damaged exhaust pipe on our boat, I asked Davey, one of the boilersmiths, if he'd help me braze a flange onto the end of a piece of copper sand pipe. Together we built an oven around the job on the forge and Davey set to with the torch, first heating the job inside the firebrick enclosure until it was cherry red, then dipping the brazing rod into the Borax and applying it to the job. But as the rod touched the copper, the whole lot just melted away and and ran into the ash on the forge. Davey started cursing and swearing, claiming that it was rotten copper, so we started again with another lump of pipe, first rebuilding the oven around the job, then after about ninety minutes, Dave lit the torch and applied the flame, but again the job just melted away. By now, Davey was jumping up and down, and feeling sure he was going to have a fit, I talked him out of trying a third time and went down the BRSA Club for a pint. I was standing at the bar, puzzling over the events of the last couple of hours, when the Bolkows lads poured in for their dinner break. I got chatting to an old mate, one of the Bolklow joiners, and explained the events of the morning - Ah-ha!' he said - 'You can't braze copper, it's got to be silver soldered. I would've thought a boilersmith would've known that! You'd best go and have a word with Teddy in the corner there; he'll sort you out…'

So I went and asked Ted, who willingly agreed. I give him the template and he told me to call at the fitters' place in Bolkows before clocking-off time at five o'clock. I went round at four and there on the bench was my job in gleaming stainless steel. The flange face was so flat; there was no need for a gasket. Teddy told me he didn't want any pay for the job, but he was partial to a bit of fish now and then, so I made sure he got well served in the Haddock Fillet department - I also made sure I never tried to braze copper again.

place in Bolkows before clocking-off time at five o'clock. I went round at four and there on the bench was my job in gleaming stainless steel. The flange face was so flat; there was no need for a gasket. Teddy told me he didn't want any pay for the job, but he was partial to a bit of fish now and then, so I made sure he got well served in the Haddock Fillet department - I also made sure I never tried to braze copper again.

(Left) This photo shows 0-6-0ST No C2 on the C & C line - riding this road was a bit like sitting on a kangaroo's back when it was in a hurry, but considering it was laid on sand it's not surprising. You can see by the way the loco is listing to starboard what a superb bit of railway it was. Note the tarpaulin cover and wooden board protecting the crew inside the cab; the C & C line was exposed to the most severe weather. After one particular bad storm, a mate and I went foraging for sea coal and found the empty line had been undercut by the sea, leaving the rails suspended over a gap of around sixty feet and two empty wagons had been unceremoniously deposited on the beach. We were forced to retire to the BRSA Club to inform the Colliery officials of the situation on the telephone, and consequently ended up there for most of the day…the N.C.B. guys were looking all over for us to show them where the catastrophe had occurred.

(Below) North Blyth Staiths Sidings 65813.

(Above) Photo of Class Q6 No 63359 at the clog end, close to the back door of the BRSA Club. The row of terraced houses are all railway houses, the first street being named after the North Eastern Railway Locomotive Engineer, Wilson Worsdell. I lived at number 26 for twenty years, right on the doorstep of North Blyth shed. You'll understand how much of a hardship it was when Cambois opened its doors - instead of falling out of bed and popping across the road to sign on, I had a mile and a quarter walk up the road! The small buildings inside the fence on the left are the old electricity sub-stations, which supplied power to the shed and houses. The small container on the right was the empty bottle store for the BRSA Club and, of course, dominating the background is North Blyth Staiths - a prominent landmark for donkey's years.

As for whose car it is? I haven't a clue, nor can I say what make of car it is. I'll leave identification to the Petrol Heads! In fact, I have never been a car person - and must confess, I have never owned one, nor had any desire to do so. It takes me all my time to cross a road nowadays…everyone seems in such an almighty rush! The identity of the make of car is solved by 'Super Sleuth' Phil Hodgetts - It is a Riley Pathfinder only in production 1953-1957, therefore the picture cannot be earlier than 53. Very similar to the Wolsley 6/90 but the rear wheelarch detail on the Pathfinder is different to the 6/90, hence confirmed as the Riley. Fred's reply is: The photo will be after about 1959 because I don't think the Q6's were at North Blyth until then, and this one looks to be in a right state - judging from the empty bunker it is for 'spares' not 'repairs', so that helps narrow it down even further.

reply is: The photo will be after about 1959 because I don't think the Q6's were at North Blyth until then, and this one looks to be in a right state - judging from the empty bunker it is for 'spares' not 'repairs', so that helps narrow it down even further.

(Right) This photograph of the two staiths pilots - 'Pups' to the enginemen - standing doing nowt makes me think that something of an extreme nature has occurred, like the staiths have fallen down or a tidal wave has swept ashore and destroyed everything in its path. But no, I suspect a seamen's' strike must be the answer. Nothing else would have stopped these locos from plying their trade, propelling fifteen or twenty wagons of coal up onto the swaying staiths, to be teemed into the bellies of the waiting ship's below.

Every day dozens of ships carried the coal to all over Europe and the Mediterranean, but mainly up the London River to the Power Stations. The Yard was a hive of activity between 0400hrs and 2200hrs, with one pilot on the staith, while the other was loading up awaiting a clear run to go up when the other came down. Meanwhile the road turns would be arriving with more trainloads of coal, then dropping into the empty line to collect a rake of thirty empty wagons for one of the local collieries. Sometimes the trains would be queuing right back to Freemans Crossing; about four miles back, waiting for the pilots to clear a road. This went on for years on end in the Sixties, and the whole affair was correlated with chalk and blackboard and ran as smooth as silk. Class J77 0-6-0Ts Nos 68392 and 68402 pose for the camera on 4th February 1958.

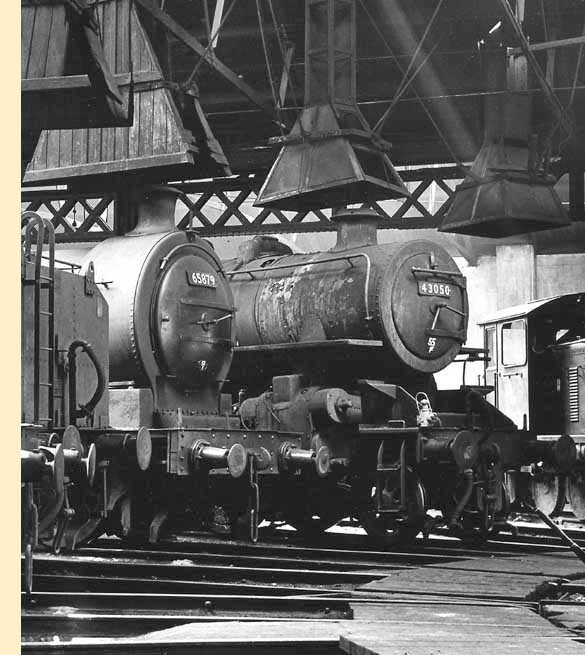

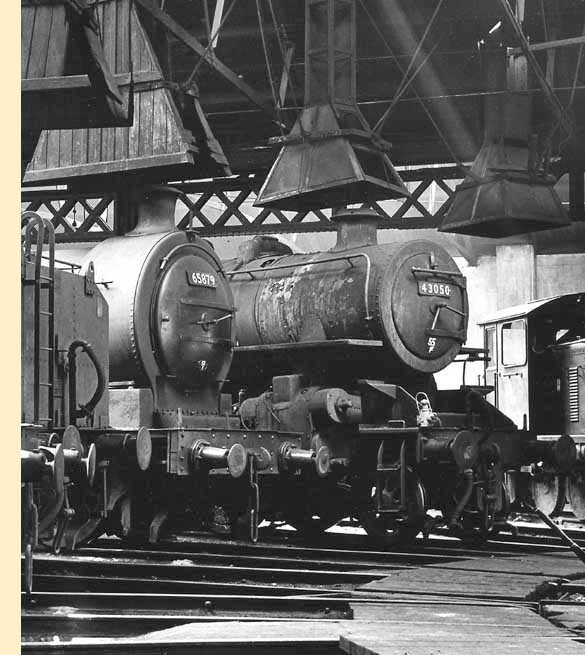

(Below) 65869 and 43140 on 27th February 1961. Here are two old, scruffy pals, one very old, the other not so old. Wilson Worsdell's NE 0-6-0 Class J27 was introduced in 1906, and belonged to a brotherhood of locomotives, built to a simple design - a straightforward pulling machine that would quite literally work until it fell to bits. I know personally of one occasion, when a cylinder cover fractured, and the loco still wanted to keep going on one cylinder. These machines simply excelled at the work they were designed for, and you have to remember that they would work for twenty hours on end, so long as the fire was cleaned when it was dirty with clinkers and its tank replenished with water, its belly full of fire. The Ivatt LMS 2-6-0 Class 4MT was introduced in 1947, some forty years later.

(Above-Below) Class J27 No 65831 is under the shutes for coal, while the shed relief fireman fills the tank with water at the column. He will have already cleaned the fire out with a solid iron scar shovel around ten feet long, and cleared the ash from the smokebox. The bent dart hanging off the handrail was used for pushing the fire from the back corners of the firebox to put it within reach of the scar shovel so that no clinker was overlooked. After the tank was full and anything up to seven tons of coal shot onto the bunker - and safely trimmed, so it could not fall off and bash somebody's brains out! - the loco will be moved down to the pit, where the fireman would go under the engine and clear the ashpan with a long rake. Then, depending on whether the loco was to go straight back out or not, he would be moved on to the turntable and the sandboxes filled, with dry sand, before being turned off and backed into a stall. The sand was dried in a large contraption that held a large fire box, and the outer casing around the firebox would be filled with damp sand, and as the sand dried, it would trickle out onto the floor, where it would be shovelled into a large silo that was warmed by the nearby furnace to prevent it damping off. The sand was used to prevent excessive wheelslip, and was operated via a coupling rod from the cab, which allowed a fine trickle from the sandbox onto the rail to improve the wheels adhesion. Later designs used steam to create a vacuum in the sand pipe to pull the sand down the pipe, and blow it under the wheel. (Below) Another North Blyth engine, No 65811, although the coalstage is neither North or South Blyth...it could be Percy Main on the Tyne.

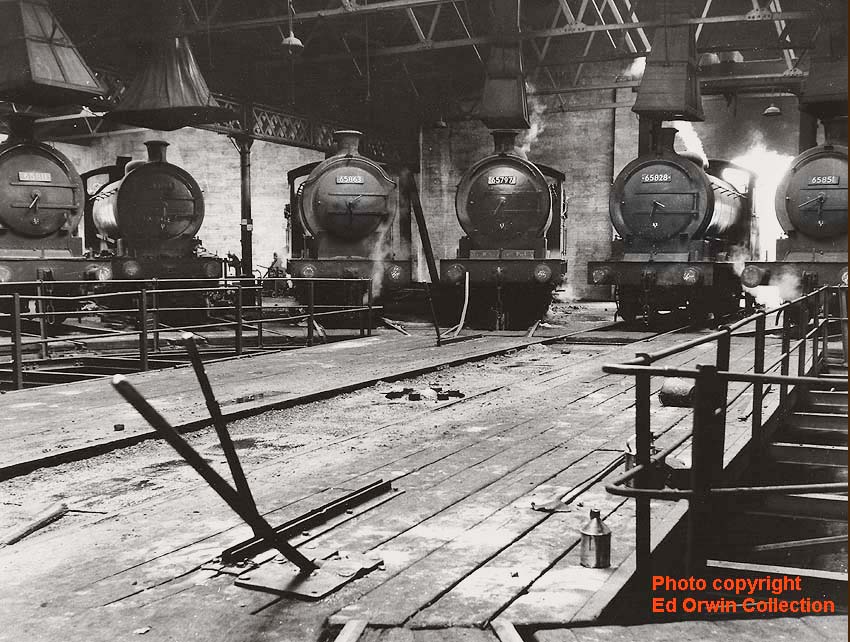

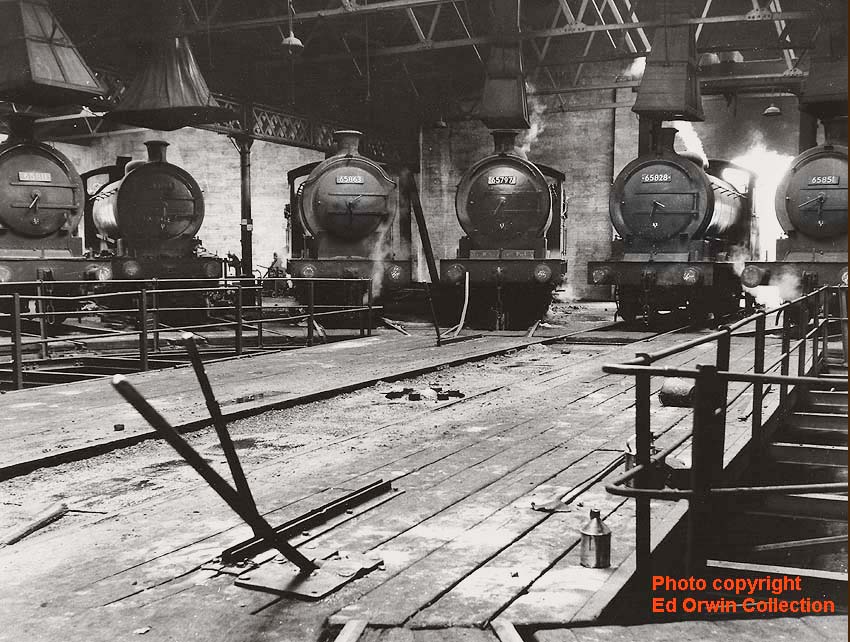

(Above-Below) Class J27s Nos 65811 and 65782 stand shoulder-to-kneecap with Class J77 0-6-0s Nos 68397, 68427 and 68399. This photograph (below) was obviously taken on a Sunday when all the J27s were having a well-deserved lie in. Seeing them all sitting in their berths like this always made me think they were having a yarn and a laugh about the past weeks work, but they couldn't, or could they? After all, we'd be doing the same in the BRSA Club, and I've seen a talking locomotive on the telly! (Below) The turntable was something you took for granted, but it was a really clever piece of engineering. It all depended on balancing the loco perfectly in the middle; when balanced a young fireman could turn the heaviest loco on his own. The levers on the turntable were the locking gear, so that the table could not move when the loco was being moved off. The other levers protruding off the table were there to give a little more leverage when pushing the table around. From left to right: Nos 65811, 65794, 65863, 65797, 65828 and 65851.

(Above) 63362 16th April 1965. This photograph of 63362 brings back a mixed bag of memories to me, as this loco was the only one that was allocated to my mate and myself. He was fresh from the shops when he first arrived - the engine, not my mate - shining black like a Guardsman's boots, and all his glands as tight as a drum, with not a breath of leaking steam. But of course that didn't last long, and he gradually merged into that scruffy anonymity, just like all the others, but he was still our engine, and we enjoyed having him. If I remember rightly, we became derailed a total of four times, including the 'Titanic' episode in the water road at West Blyth, and twice in the sidings at Linton Opencast, where the road collapsed underneath us due to the longer wheelbase of the Q6. But broadly speaking, he was very well behaved, and earned the company a great deal of money.

The small bogie parked in front of the pup (J77) was an essential piece of tackle at North Blyth. With the long hours that the engines were being worked, it was inevitable that axle boxes got hot, and consequently the lubricating oil became thinner and less able to lubricate, until sometimes the axle would actually catch fire. To combat this chain of events, the fitters came up with a programme, which involved feeling each axle when engines came onto the shed, and if any axle felt warm, the engine was laid off, turned into a stall in the shed. Next the small bogie, nicknamed the Hotbox Bogie, was pushed under the buffer beam, and the loco was jacked up and then wedged, so that the weight was taken off the axle to allow it to cool. Of course the bogie was also used to change broken springs and any job that required the engine to be lifted. Overall it was an essential piece of equipment in any steam shed.

(Above) 63397 moves off the turntable in readiness for another coal job. The Q6 was a good engine to work with and gave very little trouble, though one day, old Stanley P and I had been working a Sunday turn, which was a particularly rough job, ending up with us calling it a day because there was no coal left in the bunker. As we walked out of the shed gates at North Blyth, we saw the BRSA Club steward opening the doors for business. Stanley looked at me, raised his eyebrows questioningly, then said in a voice choked with coal dust - 'Hev ye gorr owt?'

I rummaged in my pockets, found three half crowns, Stan had five bob - and so that settled it, and into the club we went. We were halfway down our first pint, when the Club Secretary came over, waving a small notebook invitingly in our faces - 'Hev ye lads got ya Ten Free Pint tickets?' he asked.

I saw Stanley's eyebrows all a quiver again...we had only 12/6d between us, so the tickets couldn't have come at a better time - and, to cut a long story short, we ended up being slung out of the club at 45 minutes past closing time, very well served indeed - and not many Free Pint tickets left. As we stood outside the door, Stanley was adamant that their lass wouldn't let him in. He peered down the road trying to get his bearings, then started cackling that my missus would give me a green flag (that's a caution in railways) and thinking it was very funny, began giggling to himself like a drain.

Anyway, the next morning when I asked him if he had got home all right, he shook his head solemnly, and said - 'Nah! I didn't go home because I knew me-missus would've banjoed me, so I went to me-allotment and slept with me-horse to keep warm and dry out me-socks!'

It turns out that he'd ran down the ferry ramp thinking that the ferry was going away when it was coming in and got his boots full of river!

'You jammy bugger!' said I - 'Somebody trod on my fingers while I was getting on the bus!' and showed him my skinned knuckles.

'Well', said Stanley, That's another fine mess we got ourselves into...'

(Above) This photograph shows an engine and van passing North Blyth Signal Box after climbing up the shed bank. The footplatemen would have signed on an hour previously to prepare the loco for an eight-hour turn. This involved signing on at the time office, getting all the latest rumours and news from the timekeeper and of course the latest jokes doing the rounds, before studying the late notice case to find out if there were any emergency speed restrictions in operation, or to see if any alterations to working instructions had been made at short notice. The foreman would allocate a locomotive, and the fireman would then go to the stores to be issued with oil and four washed rags and two white rags (if you were lucky). On arrival at the loco both men had separate jobs - the driver would oil all the motion parts and dashpots while the fireman oiled the lubricators and the cylinder lubricators. He would also clean and tidy the cab, clean the water gauge glass protectors and start building a decent fire. He would then test the sanders and sweep any smokebox ash off the footboards - to prevent getting an eyeful. Next came trimming the coal on the tender and ensuring the tank was full, before finally cleaning the 'specs' (windows). When all the preparation was finished, the turntable would be turned to set the loco for turning out, and then up and into the van line to meet the guard, who informed them of what delightful jobs the Control had conjured up. And just to shatter any romantic illusions, this happened twenty-four hours a day, rain, hail, snow, gales, and freezing cold weather, all taken in your stride. Men would ride seven or eight miles to get to work on a bicycle, in all weathers, and then the same distance home, when they were finished.

(Above-Below) Three strangers on the Hughes-Bolkow access road in January 1965, sadly their last trip. They are ex-LMS 'Jubilee' class No 45584 North West Frontier - withdrawn from traffic at Carlisle Kingmoor in September 1964 - 'Jinty' class 0-6-0T No 47345 and an unidentified 'Patriot' class. It will take a team of four men around two days to dissect and destroy these magnificent machines, with their hissing and roaring acetylene burners and thermal lances, cynically carving them to pieces, to be turned into 'Tattie Mashers' and razor blades. Incidentally, the large white bundles lying about the place is that environmentally unfriendly substance 'blue asbestos', which used to blow all over the place whenever there was a breeze. It came from the boiler lagging on steamships that Bolkows had gobbled up. After North Blyth was demolished, the whole area was fenced off and notices erected warning of toxic waste on the site. When the Bolkows site was finally cleared, radioactive material was discovered in the mud at the quayside, believed to have come from Russian submarines that were broken up by the Hughes-Bolklow Company. They reckon that the shore crabs glowed that brightly in the dark, they had to dip their lights when passing each other! (Below) 65861, 65879, 43050 and D2312...

Footnote: My thanks to David Campbell who dropped a line regarding the line-up of locomotives in this shot. He writes: 'As far as I know no 'Patriot' class - either rebuilt or not - was cut up at North Blyth. However, rebuilt 'Jubilee' class No 45736 Phoenix ended its days there in 1965. Presumably this is what the photo is. Hope this is of use...' Corrections are always welcome. Thanks, David.

On a final note, I've included this beautifully written article, which appeared in the 'News Post Leader' (formerly Blyth News). It was written by Mrs Connie Joan Hovespian, of Windsor Road, Newbiggin by the Sea - who sums up perfectly the changes in the world and how my generation have survived...how true it all is.

Many thanks to Connie for painting such vivid word pictures of bygone days long since forgotten and especial thanks to ED Orwin for supplying the photos for this page.

'WHEN A JOINT WAS THE MEAT YOU ATE FOR SUNDAY LUNCH'

For those born before 1940, we are the survivors. We were born before television, penicillin, AIDS, polio shots, frozen food, Xerox, contact lenses, videos, freezers, vasectomies and the pill. We lived before radar, credit cards, split atoms, laser beams, and ballpoint pens, dishwashers, tumble dryers, electric blankets, air conditioning, drip dry clothes, and before man walked on the moon.

We got married first and lived together afterwards. We thought fast food was what you had at Lent. A Big Mac was an oversized raincoat and crumpet we had for tea. We existed before househusbands, computer dating, dual careers and shopping became the nation's favourite pastime. Back in our day a meaningful relationship meant getting along with your cousins and sheltered accommodation was where you waited for a bus. We were born before day care centres, group homes and disposable nappies. We had never heard of FM radio, tape decks, CDs, electric typewriters, word processing, yoghurt, health food, cholesterol, stress and men wearing earrings. For us, time-sharing meant togetherness, a chip was a piece of wood or a fried potato, hardware meant nuts and bolts and software wasn't a word.

Before 1940, 'made in Japan' meant junk; the term 'making out' referred to how well you did in your exams, a stud was what you fastened your collar or cuffs with, and going all the way meant staying on the bus until it reached the depot. Pizzas, McDonalds and instant coffee were unheard of. In our day smoking was fashionable, grass was mown, coke was kept in the coal shed, a joint was a piece of meat you had on a Sunday and pot was what you cooked it in.

Rock music was granny's lullaby; El Dorado was ice cream and a gay person was the life and soul of the party. There were four grades of toilet paper: Radio Times, Daily Despatch, Daily Herald and the Newcastle Evening Chronicle. A moneybox was a penny gas meter. We had outside toilets and transportable lightweight baths could be used in any room in the house. A porn shop was a pawnshop and a handkerchief was a coat sleeve. Footwear was constructed of leather, iron and wood. A disk jockey was a national hunt rider with a back injury. The recycling unit was the rag and bone man and an alarm was known as a knocker up. The NHS was the doctor's bill. Debt and illegitimacy were secrets. McDonald only had a farm. Central heating was a firebrick wrapped in a blanket. A kitchen unit was known as a slop stone and the top ten was the Ten Commandments.We who were born before 1940 are a hardy bunch. When you think about how much the world has changed and we have had to adapt, it's no wonder we are sometimes confused and there is a generation gap. But with the Grace of God, we have survived…'

FREDDY'S STORY CONTINUES ON THE NEXT PAGE

Introduction by David Hey

Although Fred Wagstaff is a few years older than me, the difference in our ages means little or nothing nowadays, but back in the 1950s the gap then was huge; whilst Fred was doing his National Service I was still running around in short pants collecting engine numbers.

The Fifties was a decade of 'make-do-and-mend' and most young kids were grateful for the little they had - which on the face of it, wasn't a lot - and as for career prospects? Well, those of us with a passion for steam trains wanted to be an engine driver, pure and simple...it was every boy's dream.

But all too quickly you grow into adulthood and your expectations are raised a notch higher. Gone are the innocent days of childhood; looking around you see all the material things that others have - things that you don't have yourself - and the starry-eyed notions you once had of being an engine driver begin to take on a whole new meaning. You want to make as much money as possible which means raising the bar even higher.

Then before you know it, you meet a girl and in no time at all

you're married with 2.5 kids, mortgaged up to the eyeballs and sinking beneath a mountain of debt, followed by a mid-life crisis and stuck in a job that you hate doing, and by the time you've reached retirement age, it suddenly dawns on you that no matter what you set out in life to achieve it was never enough...

you're married with 2.5 kids, mortgaged up to the eyeballs and sinking beneath a mountain of debt, followed by a mid-life crisis and stuck in a job that you hate doing, and by the time you've reached retirement age, it suddenly dawns on you that no matter what you set out in life to achieve it was never enough...Good grief, this is depressing stuff! A live wire like Freddy will firmly disapprove!

What I'm really trying to say is that today's kids have the same hopes and desires that we had at their age, but unlike the role models we aspired to emulate, there's no one comparable today.

Youngsters no longer aspire to be engine drivers; they dream of being pop stars with a smash No 1 album, glossy-mag photo shoots and excessive media scrutiny, all of which is a load of cobblers!

The abnormal amount of hero worship being lavished on today's celebrity culture is nothing short of mortifying. It only serves to trivialise the more important things in life.

That's why I've loved working with Fred. For if anyone deserves my hero worship it is the countless thousands of railaymen who did a hard, dirty job and in filty conditions, whereas the rest of us were aspiring for bigger and better things elsewhere...but do you know what? No matter what we have achieved in life, at the end of the day we all end up the same - a pile of ashes or six feet under.

Right! Enough said...during the time Fred and I have been putting together his 'Footplate Stories', he's revealed himself to be a quintessentially eccentric northern bloke, who doesn't fanny about with airs and graces, and whose wicked sense of humour makes a refreshing change from the risible PC culture we live in today. For example, just two weeks after starting on his stories, he told me - 'D'ya know what, Davey?' he said, somewhat surprised - 'I've got to thank you for getting me involved in this writing lark, I didn't think I would enjoy it so much, but I am! I feel that I've been very lucky all my life and have just about achieved everything that I've set out to do. The only thing that I didn't accomplish involved Pans People and the Three Degrees and some of the most depraved and unspeakable activities it is possible to imagine!'

See what I mean? - PC it most certainly is not, but then compared to the lack of manners, humanity, dignity, honour and respect that we see in today's unforgiving society, Fred's outspokenness is oddly reassuring. Quite simply, he tells it as it is - Fred is a fine example to us all.

But I'll let Fred take up the story…

(Above) This is the boilersmiths corner inside the roundhouse at North Blyth, and my guess is that No 65801 is having trouble with leaky boiler tubes in the smokebox. The procedure in this case would be to allow the boiler to go cold, and then insert the tube expander, which consisted of three rollers, which rotated on a conical head, and as the core was rotated it pulled the cone in and gradually the pressure tightened the tube in the smokebox boiler plate, then when the loco was fired up and everything got hot, the metal expanded, and hopefully the leak would take up.

This photo reminds me of my old days at Blyth, where a neighbourly spirit prevailed and everyone in the community was willing to help one another for next to nothing, or the favour might be returned in kind that ultimately benefited all. So when I needed to replace the damaged exhaust pipe on our boat, I asked Davey, one of the boilersmiths, if he'd help me braze a flange onto the end of a piece of copper sand pipe. Together we built an oven around the job on the forge and Davey set to with the torch, first heating the job inside the firebrick enclosure until it was cherry red, then dipping the brazing rod into the Borax and applying it to the job. But as the rod touched the copper, the whole lot just melted away and and ran into the ash on the forge. Davey started cursing and swearing, claiming that it was rotten copper, so we started again with another lump of pipe, first rebuilding the oven around the job, then after about ninety minutes, Dave lit the torch and applied the flame, but again the job just melted away. By now, Davey was jumping up and down, and feeling sure he was going to have a fit, I talked him out of trying a third time and went down the BRSA Club for a pint. I was standing at the bar, puzzling over the events of the last couple of hours, when the Bolkows lads poured in for their dinner break. I got chatting to an old mate, one of the Bolklow joiners, and explained the events of the morning - Ah-ha!' he said - 'You can't braze copper, it's got to be silver soldered. I would've thought a boilersmith would've known that! You'd best go and have a word with Teddy in the corner there; he'll sort you out…'

So I went and asked Ted, who willingly agreed. I give him the template and he told me to call at the fitters'

place in Bolkows before clocking-off time at five o'clock. I went round at four and there on the bench was my job in gleaming stainless steel. The flange face was so flat; there was no need for a gasket. Teddy told me he didn't want any pay for the job, but he was partial to a bit of fish now and then, so I made sure he got well served in the Haddock Fillet department - I also made sure I never tried to braze copper again.

place in Bolkows before clocking-off time at five o'clock. I went round at four and there on the bench was my job in gleaming stainless steel. The flange face was so flat; there was no need for a gasket. Teddy told me he didn't want any pay for the job, but he was partial to a bit of fish now and then, so I made sure he got well served in the Haddock Fillet department - I also made sure I never tried to braze copper again.(Left) This photo shows 0-6-0ST No C2 on the C & C line - riding this road was a bit like sitting on a kangaroo's back when it was in a hurry, but considering it was laid on sand it's not surprising. You can see by the way the loco is listing to starboard what a superb bit of railway it was. Note the tarpaulin cover and wooden board protecting the crew inside the cab; the C & C line was exposed to the most severe weather. After one particular bad storm, a mate and I went foraging for sea coal and found the empty line had been undercut by the sea, leaving the rails suspended over a gap of around sixty feet and two empty wagons had been unceremoniously deposited on the beach. We were forced to retire to the BRSA Club to inform the Colliery officials of the situation on the telephone, and consequently ended up there for most of the day…the N.C.B. guys were looking all over for us to show them where the catastrophe had occurred.

(Below) North Blyth Staiths Sidings 65813.

(Above) Photo of Class Q6 No 63359 at the clog end, close to the back door of the BRSA Club. The row of terraced houses are all railway houses, the first street being named after the North Eastern Railway Locomotive Engineer, Wilson Worsdell. I lived at number 26 for twenty years, right on the doorstep of North Blyth shed. You'll understand how much of a hardship it was when Cambois opened its doors - instead of falling out of bed and popping across the road to sign on, I had a mile and a quarter walk up the road! The small buildings inside the fence on the left are the old electricity sub-stations, which supplied power to the shed and houses. The small container on the right was the empty bottle store for the BRSA Club and, of course, dominating the background is North Blyth Staiths - a prominent landmark for donkey's years.

As for whose car it is? I haven't a clue, nor can I say what make of car it is. I'll leave identification to the Petrol Heads! In fact, I have never been a car person - and must confess, I have never owned one, nor had any desire to do so. It takes me all my time to cross a road nowadays…everyone seems in such an almighty rush! The identity of the make of car is solved by 'Super Sleuth' Phil Hodgetts - It is a Riley Pathfinder only in production 1953-1957, therefore the picture cannot be earlier than 53. Very similar to the Wolsley 6/90 but the rear wheelarch detail on the Pathfinder is different to the 6/90, hence confirmed as the Riley. Fred's

reply is: The photo will be after about 1959 because I don't think the Q6's were at North Blyth until then, and this one looks to be in a right state - judging from the empty bunker it is for 'spares' not 'repairs', so that helps narrow it down even further.

reply is: The photo will be after about 1959 because I don't think the Q6's were at North Blyth until then, and this one looks to be in a right state - judging from the empty bunker it is for 'spares' not 'repairs', so that helps narrow it down even further. (Right) This photograph of the two staiths pilots - 'Pups' to the enginemen - standing doing nowt makes me think that something of an extreme nature has occurred, like the staiths have fallen down or a tidal wave has swept ashore and destroyed everything in its path. But no, I suspect a seamen's' strike must be the answer. Nothing else would have stopped these locos from plying their trade, propelling fifteen or twenty wagons of coal up onto the swaying staiths, to be teemed into the bellies of the waiting ship's below.

Every day dozens of ships carried the coal to all over Europe and the Mediterranean, but mainly up the London River to the Power Stations. The Yard was a hive of activity between 0400hrs and 2200hrs, with one pilot on the staith, while the other was loading up awaiting a clear run to go up when the other came down. Meanwhile the road turns would be arriving with more trainloads of coal, then dropping into the empty line to collect a rake of thirty empty wagons for one of the local collieries. Sometimes the trains would be queuing right back to Freemans Crossing; about four miles back, waiting for the pilots to clear a road. This went on for years on end in the Sixties, and the whole affair was correlated with chalk and blackboard and ran as smooth as silk. Class J77 0-6-0Ts Nos 68392 and 68402 pose for the camera on 4th February 1958.

(Below) 65869 and 43140 on 27th February 1961. Here are two old, scruffy pals, one very old, the other not so old. Wilson Worsdell's NE 0-6-0 Class J27 was introduced in 1906, and belonged to a brotherhood of locomotives, built to a simple design - a straightforward pulling machine that would quite literally work until it fell to bits. I know personally of one occasion, when a cylinder cover fractured, and the loco still wanted to keep going on one cylinder. These machines simply excelled at the work they were designed for, and you have to remember that they would work for twenty hours on end, so long as the fire was cleaned when it was dirty with clinkers and its tank replenished with water, its belly full of fire. The Ivatt LMS 2-6-0 Class 4MT was introduced in 1947, some forty years later.

(Above-Below) Class J27 No 65831 is under the shutes for coal, while the shed relief fireman fills the tank with water at the column. He will have already cleaned the fire out with a solid iron scar shovel around ten feet long, and cleared the ash from the smokebox. The bent dart hanging off the handrail was used for pushing the fire from the back corners of the firebox to put it within reach of the scar shovel so that no clinker was overlooked. After the tank was full and anything up to seven tons of coal shot onto the bunker - and safely trimmed, so it could not fall off and bash somebody's brains out! - the loco will be moved down to the pit, where the fireman would go under the engine and clear the ashpan with a long rake. Then, depending on whether the loco was to go straight back out or not, he would be moved on to the turntable and the sandboxes filled, with dry sand, before being turned off and backed into a stall. The sand was dried in a large contraption that held a large fire box, and the outer casing around the firebox would be filled with damp sand, and as the sand dried, it would trickle out onto the floor, where it would be shovelled into a large silo that was warmed by the nearby furnace to prevent it damping off. The sand was used to prevent excessive wheelslip, and was operated via a coupling rod from the cab, which allowed a fine trickle from the sandbox onto the rail to improve the wheels adhesion. Later designs used steam to create a vacuum in the sand pipe to pull the sand down the pipe, and blow it under the wheel. (Below) Another North Blyth engine, No 65811, although the coalstage is neither North or South Blyth...it could be Percy Main on the Tyne.

(Above-Below) Class J27s Nos 65811 and 65782 stand shoulder-to-kneecap with Class J77 0-6-0s Nos 68397, 68427 and 68399. This photograph (below) was obviously taken on a Sunday when all the J27s were having a well-deserved lie in. Seeing them all sitting in their berths like this always made me think they were having a yarn and a laugh about the past weeks work, but they couldn't, or could they? After all, we'd be doing the same in the BRSA Club, and I've seen a talking locomotive on the telly! (Below) The turntable was something you took for granted, but it was a really clever piece of engineering. It all depended on balancing the loco perfectly in the middle; when balanced a young fireman could turn the heaviest loco on his own. The levers on the turntable were the locking gear, so that the table could not move when the loco was being moved off. The other levers protruding off the table were there to give a little more leverage when pushing the table around. From left to right: Nos 65811, 65794, 65863, 65797, 65828 and 65851.

(Above) 63362 16th April 1965. This photograph of 63362 brings back a mixed bag of memories to me, as this loco was the only one that was allocated to my mate and myself. He was fresh from the shops when he first arrived - the engine, not my mate - shining black like a Guardsman's boots, and all his glands as tight as a drum, with not a breath of leaking steam. But of course that didn't last long, and he gradually merged into that scruffy anonymity, just like all the others, but he was still our engine, and we enjoyed having him. If I remember rightly, we became derailed a total of four times, including the 'Titanic' episode in the water road at West Blyth, and twice in the sidings at Linton Opencast, where the road collapsed underneath us due to the longer wheelbase of the Q6. But broadly speaking, he was very well behaved, and earned the company a great deal of money.

The small bogie parked in front of the pup (J77) was an essential piece of tackle at North Blyth. With the long hours that the engines were being worked, it was inevitable that axle boxes got hot, and consequently the lubricating oil became thinner and less able to lubricate, until sometimes the axle would actually catch fire. To combat this chain of events, the fitters came up with a programme, which involved feeling each axle when engines came onto the shed, and if any axle felt warm, the engine was laid off, turned into a stall in the shed. Next the small bogie, nicknamed the Hotbox Bogie, was pushed under the buffer beam, and the loco was jacked up and then wedged, so that the weight was taken off the axle to allow it to cool. Of course the bogie was also used to change broken springs and any job that required the engine to be lifted. Overall it was an essential piece of equipment in any steam shed.

(Above) 63397 moves off the turntable in readiness for another coal job. The Q6 was a good engine to work with and gave very little trouble, though one day, old Stanley P and I had been working a Sunday turn, which was a particularly rough job, ending up with us calling it a day because there was no coal left in the bunker. As we walked out of the shed gates at North Blyth, we saw the BRSA Club steward opening the doors for business. Stanley looked at me, raised his eyebrows questioningly, then said in a voice choked with coal dust - 'Hev ye gorr owt?'

I rummaged in my pockets, found three half crowns, Stan had five bob - and so that settled it, and into the club we went. We were halfway down our first pint, when the Club Secretary came over, waving a small notebook invitingly in our faces - 'Hev ye lads got ya Ten Free Pint tickets?' he asked.

I saw Stanley's eyebrows all a quiver again...we had only 12/6d between us, so the tickets couldn't have come at a better time - and, to cut a long story short, we ended up being slung out of the club at 45 minutes past closing time, very well served indeed - and not many Free Pint tickets left. As we stood outside the door, Stanley was adamant that their lass wouldn't let him in. He peered down the road trying to get his bearings, then started cackling that my missus would give me a green flag (that's a caution in railways) and thinking it was very funny, began giggling to himself like a drain.

Anyway, the next morning when I asked him if he had got home all right, he shook his head solemnly, and said - 'Nah! I didn't go home because I knew me-missus would've banjoed me, so I went to me-allotment and slept with me-horse to keep warm and dry out me-socks!'

It turns out that he'd ran down the ferry ramp thinking that the ferry was going away when it was coming in and got his boots full of river!

'You jammy bugger!' said I - 'Somebody trod on my fingers while I was getting on the bus!' and showed him my skinned knuckles.

'Well', said Stanley, That's another fine mess we got ourselves into...'

(Above) This photograph shows an engine and van passing North Blyth Signal Box after climbing up the shed bank. The footplatemen would have signed on an hour previously to prepare the loco for an eight-hour turn. This involved signing on at the time office, getting all the latest rumours and news from the timekeeper and of course the latest jokes doing the rounds, before studying the late notice case to find out if there were any emergency speed restrictions in operation, or to see if any alterations to working instructions had been made at short notice. The foreman would allocate a locomotive, and the fireman would then go to the stores to be issued with oil and four washed rags and two white rags (if you were lucky). On arrival at the loco both men had separate jobs - the driver would oil all the motion parts and dashpots while the fireman oiled the lubricators and the cylinder lubricators. He would also clean and tidy the cab, clean the water gauge glass protectors and start building a decent fire. He would then test the sanders and sweep any smokebox ash off the footboards - to prevent getting an eyeful. Next came trimming the coal on the tender and ensuring the tank was full, before finally cleaning the 'specs' (windows). When all the preparation was finished, the turntable would be turned to set the loco for turning out, and then up and into the van line to meet the guard, who informed them of what delightful jobs the Control had conjured up. And just to shatter any romantic illusions, this happened twenty-four hours a day, rain, hail, snow, gales, and freezing cold weather, all taken in your stride. Men would ride seven or eight miles to get to work on a bicycle, in all weathers, and then the same distance home, when they were finished.

(Above-Below) Three strangers on the Hughes-Bolkow access road in January 1965, sadly their last trip. They are ex-LMS 'Jubilee' class No 45584 North West Frontier - withdrawn from traffic at Carlisle Kingmoor in September 1964 - 'Jinty' class 0-6-0T No 47345 and an unidentified 'Patriot' class. It will take a team of four men around two days to dissect and destroy these magnificent machines, with their hissing and roaring acetylene burners and thermal lances, cynically carving them to pieces, to be turned into 'Tattie Mashers' and razor blades. Incidentally, the large white bundles lying about the place is that environmentally unfriendly substance 'blue asbestos', which used to blow all over the place whenever there was a breeze. It came from the boiler lagging on steamships that Bolkows had gobbled up. After North Blyth was demolished, the whole area was fenced off and notices erected warning of toxic waste on the site. When the Bolkows site was finally cleared, radioactive material was discovered in the mud at the quayside, believed to have come from Russian submarines that were broken up by the Hughes-Bolklow Company. They reckon that the shore crabs glowed that brightly in the dark, they had to dip their lights when passing each other! (Below) 65861, 65879, 43050 and D2312...

Footnote: My thanks to David Campbell who dropped a line regarding the line-up of locomotives in this shot. He writes: 'As far as I know no 'Patriot' class - either rebuilt or not - was cut up at North Blyth. However, rebuilt 'Jubilee' class No 45736 Phoenix ended its days there in 1965. Presumably this is what the photo is. Hope this is of use...' Corrections are always welcome. Thanks, David.

On a final note, I've included this beautifully written article, which appeared in the 'News Post Leader' (formerly Blyth News). It was written by Mrs Connie Joan Hovespian, of Windsor Road, Newbiggin by the Sea - who sums up perfectly the changes in the world and how my generation have survived...how true it all is.

Many thanks to Connie for painting such vivid word pictures of bygone days long since forgotten and especial thanks to ED Orwin for supplying the photos for this page.

'WHEN A JOINT WAS THE MEAT YOU ATE FOR SUNDAY LUNCH'

For those born before 1940, we are the survivors. We were born before television, penicillin, AIDS, polio shots, frozen food, Xerox, contact lenses, videos, freezers, vasectomies and the pill. We lived before radar, credit cards, split atoms, laser beams, and ballpoint pens, dishwashers, tumble dryers, electric blankets, air conditioning, drip dry clothes, and before man walked on the moon.

We got married first and lived together afterwards. We thought fast food was what you had at Lent. A Big Mac was an oversized raincoat and crumpet we had for tea. We existed before househusbands, computer dating, dual careers and shopping became the nation's favourite pastime. Back in our day a meaningful relationship meant getting along with your cousins and sheltered accommodation was where you waited for a bus. We were born before day care centres, group homes and disposable nappies. We had never heard of FM radio, tape decks, CDs, electric typewriters, word processing, yoghurt, health food, cholesterol, stress and men wearing earrings. For us, time-sharing meant togetherness, a chip was a piece of wood or a fried potato, hardware meant nuts and bolts and software wasn't a word.

Before 1940, 'made in Japan' meant junk; the term 'making out' referred to how well you did in your exams, a stud was what you fastened your collar or cuffs with, and going all the way meant staying on the bus until it reached the depot. Pizzas, McDonalds and instant coffee were unheard of. In our day smoking was fashionable, grass was mown, coke was kept in the coal shed, a joint was a piece of meat you had on a Sunday and pot was what you cooked it in.

Rock music was granny's lullaby; El Dorado was ice cream and a gay person was the life and soul of the party. There were four grades of toilet paper: Radio Times, Daily Despatch, Daily Herald and the Newcastle Evening Chronicle. A moneybox was a penny gas meter. We had outside toilets and transportable lightweight baths could be used in any room in the house. A porn shop was a pawnshop and a handkerchief was a coat sleeve. Footwear was constructed of leather, iron and wood. A disk jockey was a national hunt rider with a back injury. The recycling unit was the rag and bone man and an alarm was known as a knocker up. The NHS was the doctor's bill. Debt and illegitimacy were secrets. McDonald only had a farm. Central heating was a firebrick wrapped in a blanket. A kitchen unit was known as a slop stone and the top ten was the Ten Commandments.We who were born before 1940 are a hardy bunch. When you think about how much the world has changed and we have had to adapt, it's no wonder we are sometimes confused and there is a generation gap. But with the Grace of God, we have survived…'

FREDDY'S STORY CONTINUES ON THE NEXT PAGE

Polite notice: All text and photographs are protected by copyright and reproduction is prohibited without the prior consent of the © owners. If you wish to discuss using the contents of this page the email address is below. Please note - this is not a 'clickable' mail-to link via Outlook Express. You will have to email manually.

fwagstaff636@btinternet.com

dheycollection@ntlworld.com